This story is the first of the two-part A Hollow Promise series on the lack of effective resources for the homeless in Madison.

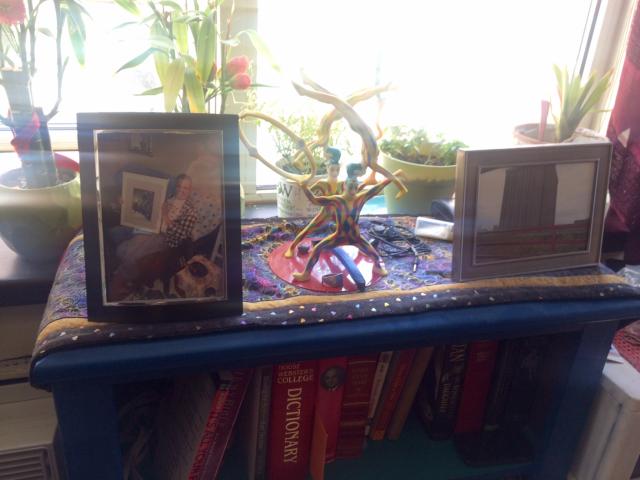

The support of his family helped John Terry escape homelessness; many of Madison's homeless are not so lucky. (Luke Schaetzel/Madison Commons)

The support of his family helped John Terry escape homelessness; many of Madison's homeless are not so lucky. (Luke Schaetzel/Madison Commons)

The struggle of Madison’s homeless population has come into light more recently as the homeless population has surged. In recent years the city has become much more reliant on volunteer services or for-profit resources, which may not be a viable option for those living on the streets.

John Terry Jr. has battled mental health problems, addiction and homelessness. Unlike many who have also struggled with these issues, he has had a support system to help him on his road to recovery and self-sustainability.

Terry’s journey from the streets to sobriety was not easy though, even with the support he has. His story also exposes how those without such support systems still struggle to find their way.

A disease takes hold

It is a cliché, but it rings true for Terry: things got worse before they got better. When Terry was younger, he moved out of Wisconsin and to California and had a lot going for him. He had a job at an insurance agency, friends and a steady relationship with a woman he loved. The insurance agency even offered to send Terry to college, completely paid for.

But Terry’s undiagnosed mental health issues and alcoholism began to take hold. He ended up moving back to Wisconsin and started working for his father. The more he drank, the more unreliable he became at work, and Terry’s life slowly began to fall apart.

Realizing he needed help, and with the support of his family, Terry took three visits to Alcohab, a transitional home for sober living in Janesville. Those three visits cost his father over $2,000. Treatments at Alcohab did not work, so Terry tried Alcoholics Anonymous.

“I do not like people who bullshit me and have ‘all the answers’ and you find that in AA. ‘Read the book; these are stories that are supposed to keep you sober’ but they’re all stories that happened in the 1930s,” Terry said. “It’s just not for me.”

After two failed recovery attempts, Terry began to ruin relationships with those in his family.

“I was stealing left and right from my family,” Terry said. At this point, he was kicked out of his house and forced to live on the streets of Madison.

Getting connected with help

Without his family’s support, Terry may never have reached the services he needed.

Terry’s brother first linked him up with Connections Counseling. There, he was diagnosed with bipolar and schizophrenic disorders. In addition to medication, the doctor recommended the therapy which led Terry to independence and recovery.

Prior to coming to Connections Counseling Terry said his life was a blur. “A lot of things happened in slow-motion,” he said. He recalled days spent drinking and nights living on the street.

Connections Counseling uses a unique dual diagnosis which gets to the root causes of addiction by treating both the addiction and the associated mental health issues.

Terry now lives in his own apartment at Porchlight, which for many years was funded by his father. (Luke Schaetzel /Madison Commons)

Terry now lives in his own apartment at Porchlight, which for many years was funded by his father. (Luke Schaetzel /Madison Commons)

Connections tries to provide funding for low-income patients through its non-profit Recovery Foundation. According to Shelly Dutch, founder of Connections, at least 15 current patients are funded through the foundation. However, patients without insurance are not eligible for the medical treatments that make dual diagnosis counseling so effective.

While treatment for mental health and addiction could move him in the right direction, Terry still needed housing.

Porchlight, a volunteer-based, nonprofit organization, is Madison’s largest provider of homelessness resources. Terry pays modest rent to live in an apartment at Porchlight’s headquarters. Terry now uses disability checks to pay his rent, but for many years, his father funded his living.

Jessica Pastelin, the development director of Porchlight, recognizes how unique such sustained help is.

“That’s a rarity,” Pastelin said. “Some people will have support systems, but a lot of times it won’t be as extensive as [Terry’s] because he has brothers and parents.”

The monthly rents from tenants make up the vast majority of Porchlight’s funding; funding from the state and federal governments is a small portion.This trend of individuals and organizations stepping in where the current government is not has become the normal in Madison.

|

|

|

Welcome to the Madison Commons, a website designed to provide news and information about all of Madison's neighborhoods and a crossroads for the discussion of community issues. The name comes from the idea of a village commons, a place for news, talk, debate, and some entertainment, too, that's open to everyone.

All rights reserved. Read more about the Madison Commons and its partners.