When students at Midvale Elementary enter their schoolyard, they are greeted by a veritable fairytale. Delicate white moonflowers glow from the outer space garden patch. A beanstalk reaches into the sky above them. A sunflower hut beckons their imaginations.

But the children aren’t here to play. Carrying rulers, pencils and paper, they head for the math garden where they will track the growth of different plants—and maybe dally to pluck some fresh raspberries along the way.

The Midvale schoolyard is one of dozens of outdoor classrooms sprouting up around Madison, where teachers and students are experimenting with hands-on learning. Educators and researchers say such school gardens benefit children in multiple ways, encouraging them to eat healthier foods, be more active and learn applicable lessons about science, math and nutrition.

About 30 percent of Wisconsin’s low-income children ages 2 to 4 are overweight or obese, according to Amy Meinen, a nutrition coordinator for the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. She said school gardens help students develop healthy eating habits at an early age, which is important to maintaining a healthy weight in the long term.

“The longer the weight stays on someone’s frame, the more likely they are to be obese as an adult,” Meinen said. “If you put healthy food in the kid’s environment, they don’t realize this is a strategy to get kids to eat fruits and vegetables. The choice is easy.”

If children grow the fruits and vegetables themselves, she said, it makes the choice to eat them more desirable, with the extra motivation of pride and accomplishment.

Meinen shared this information with school garden supporters from across the state March 5, during the Youth Grow Local Conference at the Goodman Community Center. The conference was sponsored by  Conference participants stand on the skeleton of a hoop house to stay dry on a tour of the Goodman Community Center gardens.Community GroundWorks, a local nonprofit that promotes nutrition and education through urban gardening. About 100 people attended workshops on topics such as how to start youth gardens, involve teachers in such initiatives and bring fresh produce into the classroom.

Conference participants stand on the skeleton of a hoop house to stay dry on a tour of the Goodman Community Center gardens.Community GroundWorks, a local nonprofit that promotes nutrition and education through urban gardening. About 100 people attended workshops on topics such as how to start youth gardens, involve teachers in such initiatives and bring fresh produce into the classroom.

Sam Dennis, an associate professor of landscape architecture at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said school gardens help children make connections between what grows in the ground and what they see on their plate.

“If a kid is involved with the act of gardening, if they’re familiar with the carrot coming out of the ground, they’ll eat it,” he said.

Another benefit of gardening is the physical activity. Nathan Larson, education director at Community GroundWorks, uses the term “meaningful fitness” to describe the exercise students get in the garden—climbing a tree to pick apples, pulling a wheelbarrow, or digging a hole.

“If you think about the movements in the garden, it’s kind of similar to yoga poses—trying to reach that weed just so,” said Dennis, who taught a workshop with Meinen called “Garden Fit.”

Gardening is fairly simple with the right ingredients—healthy soil, seeds, water, sun, hands. But gardening in schools is more complicated. Advocates for outdoor classrooms face plenty of hurdles, including a short growing season and logistical concerns.

The initiative to start a school garden typically comes from a group of motivated parents. Together, they navigate the complex world of school boards and budgets, unenthusiastic parents and teachers, grant applications and curriculum recommendations.

“One thing I’ve learned about the work I do is it’s messy and ambiguous,” said Rachel Martin, parent and co-founder of the Midvale gardens.

Gardens tend to be funded by a patchwork of grants and tended by people with diverse skill sets. Usually working as volunteers, these parents and community members are often driven by one another.

“I like creating community and making the world a better place,” Martin said. “You start and then you keep going because of everyone around you.”

The team of parents at Midvale asked the school’s instructional resource teacher Mary Kay Johnson to write curriculum for teachers to employ in the gardens. Although Johnson said she does not like gardening, she said she did enjoy designing lessons for the garden, excited by the innovative possibilities and driven by the passion of the parents.

“They’re so very generous with their time,” Johnson said. “There’s no stopping what they’re doing. A lot of the parents don’t even have kids at Midvale; they’re just doing it for the good of the garden.”

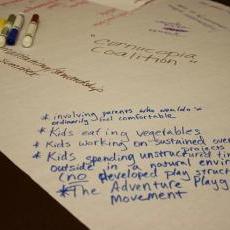

In one workshop, attendees scribbled down ideas for promoting and sustaining school gardens.

In one workshop, attendees scribbled down ideas for promoting and sustaining school gardens.

At the Youth Grow Local Conference, Martin led a workshop to find out what motivates volunteers like her. She covered tables with long sheets of butcher paper and passed out markers. She asked everyone to write down why they worked on youth gardens.

From the writings and conversations, common ideologies emerged. People talked about feeling a connection to the land, place and community in addition to the more measurable benefits of nutrition, exercise and effective learning.

When Kathy Brozyna enrolled her kids at Van Hise Elementary last summer, they started volunteering in the garden there. She said that experience introduced her family to a community of friends, and helped her teach her kids important life lessons.

“I like being able to teach my kids about seasons and cycles,” Brozyna said. “I like them to see that something can die in the winter and come back in the spring.”

Over the posters and markers, conversations grew as people discussed their experiences and listened eagerly to others. Many seemed to feel comforted that their concerns were shared by others.

“Something I struggle with is—I can bring it in the classroom, but what does it translate to at home?” said Bjorn Bergman, a Farm to Schools employee in Vernon County.

“Yeah, I take every opportunity I have to make an activity into a family activity instead of just for kids,” said Julie King, coordinator of the rooftop garden at the Madison Children’s Museum. “In an environment like the children’s museum, kids think it’s fun, but you don’t really know if it goes home with them.”

People also swapped tips, such as how to write an effective grant or minimize compost odor by adding shredded office paper. Nearly every time someone raised a dilemma, another person offered a solution.

While some mentioned lofty visions of a healthier planet and a stronger education system, most conversations focused on local projects where people could have a tangible impact. Martin said events such as the conference help build community and encourage individuals to work together to accomplish what they can’t do alone.

“I’m an optimist,” Martin said. “When I really think about the reality and how few people are engaged in it, I think, this sucks. But you focus on what you can change. I like models that focus on the local community because that’s where you have power.”

In school communities with driven volunteers like Martin, school gardens can develop quickly and successfully.

But what happens in communities that don’t have the volunteers or resources to start or sustain a school garden? What makes a garden succeed, and what can be done to make gardens attainable for more schools?

These questions are addressed in part two of this series.

|

|

|

Welcome to the Madison Commons, a website designed to provide news and information about all of Madison's neighborhoods and a crossroads for the discussion of community issues. The name comes from the idea of a village commons, a place for news, talk, debate, and some entertainment, too, that's open to everyone.

All rights reserved. Read more about the Madison Commons and its partners.