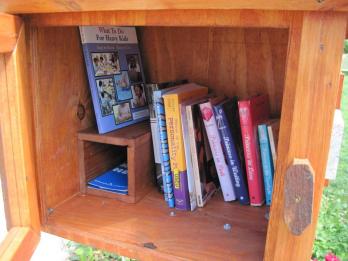

Photo: Chris MalinaNo library card is required, no membership dues apply, and there are definitely no late fees. Simply “take a book, return a book,” and you will follow the only guideline of the Little Free Library project, a community outreach program designed to bring communities together through the simple act of reading.

Photo: Chris MalinaNo library card is required, no membership dues apply, and there are definitely no late fees. Simply “take a book, return a book,” and you will follow the only guideline of the Little Free Library project, a community outreach program designed to bring communities together through the simple act of reading.

The Little Free Library Project began in Hudson, Wisc., when Todd Bol wanted to slow down traffic on his street. Each Little Free Library differs in size and appearance, but usually takes the basic shape of an oversized birdhouse on a post, with a Plexiglas door on the front for easy viewing of the books inside. Bol built and opened the first Little Free Library, decorating it to resemble an old-fashioned one-room schoolhouse in honor of his mother.

After hosting a garage sale at his home Bol realized the popularity of the library.

“I had many people come up and tell me how wonderful the library is and people got really excited about it,” Bol said.

Bol decided to test the idea in Madison, and called Rick Brooks, an Outreach Program Manager at the University of Wisconsin Madison, for help. The duo placed Madison’s first Little Free Library outside Absolutely Art on Atwood Avenue, and the Little Free Library project was born.

Potential library hosts can purchase pre-built Little Free Libraries through the project’s website, or use the building plans available on the site to craft their own. Once registered, each Little Free Library is issued a sign bearing the name “Little Free Library” and the project’s slogan, “Take a book, return a book.” Photo: Chris Malina

Photo: Chris Malina

One of these libraries, designed to resemble an Amish cabin, found a home outside Indie Coffee on Regent Street in Madison. J.J. Kilmer, Indie Coffee’s owner and the host of the library, felt the idea behind the Little Free Library project was perfect for her coffee shop.

“We loved the idea of recycling perfectly valuable books, and felt it'd also be a great spark for community cohesion,” Kilmer said.

After finding early success in Madison, The Little Free Library gained momentum this July when it won a $1,000 grant from Awesome Chicago, a contest designed to recognize projects that make the community “awesomer.” As a result, the Little Free Library project was able to put up six of their libraries in Chicago, Bol said.

Soon after, the Little Free Library gained media attention in many midwestern cities such as Chicago, Madison, and the Twin Cities, and co-founders Bol and Brooks appeared on Wisconsin Public Radio’s talk show Here on Earth: Radio Without Borders in September. The talk show appearance sparked nearly 5,000 hits on the Little Free Library website and led to 76 requests for signs for new Little Free Libraries.

The support of community members and volunteers has allowed this non-profit company to expand from a single free library in Hudson to at least 300 of free libraries across the United States.

“We have gotten volunteers from across the country helping us with building designs, helping us with our website, helping us with public relations, we’ve had all kinds of help from all kinds of places, which has been just fantastic,” Bol said.

Many of what Bol calls “rogue libraries” have emerged, built by individuals who heard about the project and wanted to include it in their communities. As the Little Free Library project becomes aware of these “rogue libraries,” Bol sends them library signs and adds them to the Little Free Library network.

Bol and Brooks both believe that community building is the heart of the Little Free Library Project.

“People are comfortable enough to come up and talk about libraries and books and reading and school, and they have a common interest,” Bol said. “People constantly tell us they meet people and talk to them in ten or fifteen minutes more than they have the whole five years they’ve lived somewhere or the whole 20 years they’ve lived somewhere.”

Many of the Little Free Libraries even have their own individual Facebook pages, created by community members, where people can contact each other and share their experiences with the libraries.

Photo: Chris MalinaWith community building in mind, The Little Free Library project is currently working to launch Bookus Binder, a venture that is intended to further involve volunteers and readers.

Photo: Chris MalinaWith community building in mind, The Little Free Library project is currently working to launch Bookus Binder, a venture that is intended to further involve volunteers and readers.

Bookus Binder is a hero that Bol compared to Johnny Appleseed. Instead of spread fruit trees, Bookus Binder spreads knowledge via books and libraries.

The Little Free Library project will be asking people from all over to write stories about Bookus, intending to create a sort of “Chicken Soup” compilation of stories about the power of reading and literacy.

“What’s interesting about Bookus is he’s a bit of a chameleon,” Bol said. “Bookus will change to whatever the community is. It can be young, old, black, white, Hispanic, Muslim, whatever.”

In addition to the development of Bookus Binder, the future of the Little Free Library Project will include more involvement outside of the United States, according to the co-founders.

“I think we’ve got a lot of international appeal,” Bol said. “It’s a really nice community outreach that’s a real, live common ground for people who want to talk about literacy and books and things they read.”

The Little Free Library project already has connections in Germany, Australia, England, Canada, Sri Lanka and Nepal, Brooks said.

A Little Free Library even sits on an old medieval castle bridge in Hamburg, Germany.

The project hopes to continue making an impact in communities across the United States and worldwide.

|

|

|

Welcome to the Madison Commons, a website designed to provide news and information about all of Madison's neighborhoods and a crossroads for the discussion of community issues. The name comes from the idea of a village commons, a place for news, talk, debate, and some entertainment, too, that's open to everyone.

All rights reserved. Read more about the Madison Commons and its partners.