When Milele Chikasa Anana founded her community development magazine UMOJA in Madison in 1990, it was a bigger gamble than it was a sure success. She started UMOJA as a newsletter of upcoming events in the community, printed on an 8x10 sheet of paper. But her passion pushed her to launch the Black community-focused magazine, while still working as an information technology specialist at a bus company.

While the typical image of an entrepreneur may be running a brick-and-mortar business with paid employees, black entrepreneurs often adopt a different approach: “team of me.” More officially referred to as sole proprietorship, this business model includes only one employee, the owner.

In its 27th year of publishing and over 300 issues, UMOJA Magazine is a part of the 30 percent of black businesses nationally that have sustained for over 10 years, in comparison to nearly 50 percent of white entrepreneurial businesses. So while the magazine’s long-standing success is a rarity, Anana’s preservation as a sole proprietor is commonplace as 95 percent of black businesses do not hire employees outside the owner.

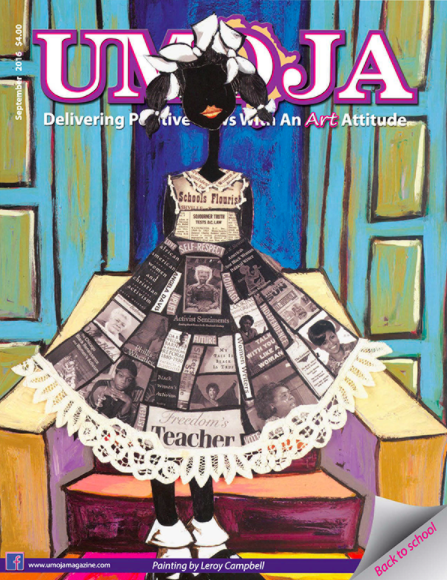

Previous cover of UMOJA magazine.

Previous cover of UMOJA magazine.

The U.S. Census Bureau reported in 2012 that black-owned businesses create the least amount of jobs compared to other races and earn the least annual revenue. It’s not entirely surprising, considering the wealth disparity and difficulties faced to even jump-start businesses.

Kicking off the publication with just the money in her pocket to go towards printing at Kinkos, it took a few years before Anana could pursue UMOJA full-time. By working out of her home on Madison’s east side, Anana saved the money that is typically drained from brick-and-mortar businesses in their beginnings.

“I still had a job when I started. I’d come home in the evenings and print all night,” she said.

These initial financial sacrifices helped her realize her idea for a magazine about the black experience in Madison, and address her dissatisfaction with local media outlets and their media portrayals of Black people limited to athletes and mugshots.

Her frustration in the lacking media sector for black people led to a part-time pursuit of stories exclusively about and written by the black community. Even though she had no prior experience in journalism or publishing, she had the passion and the community had the need for more uplifting coverage of local African-Americans.

“I knew that wasn’t the whole spectrum of our existence,” Anana said. “I had been talking to the Wisconsin State Journal and The Cap Times, but they weren’t hearing me. So I decided that I would make something beautiful and inspiring for Black people.”

In 2015, the City of Madison passed a resolution commending the achievements and community contributions of UMOJA publisher and editor Milele Chikasa Anana, and honoring UMOJA magazine on the celebration of its twenty-fifth anniversary.

Anana’s part-time job and working from home minimized the risk she was taking, providing collateral through the bumpy course of managing a magazine. The average cost of starting a business is $30,000, a steep expense when compared to the black household median wealth of $11,000, according to the Pew Research Center and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis in 2013.

“Black people, especially in Madison, earn less than other races. As a result there’s less wealth and because of that there’s less flex capital to branch out and start a business with enough stability and cushion to succeed or fail and still succeed,” said Eric Upchurch, former interim executive director of Madison’s Black Chamber of Commerce.

Carmell Jackson, owner of the former Madison restaurant Melly Mell’s, opened the soul food venue in 2010 using her inheritance and a small business grant awarded to minority business owners. Jackson was one of few minority entrepreneurs able to kickstart a business without loans. Those lacking the financial capital must seek support in the form of small business loans and grants, a process that can hinder a business altogether if unsuccessful.

The Small Business Administration’s Office of Advocacy reported in 2013 that blacks and Hispanics are less likely to be approved than whites, thus, black entrepreneurs tend to start their companies with less money than white entrepreneurs, relying more on personal wealth than on outside lenders or investors.

For Jackson, the difficulty wasn’t in starting the business but maintaining it. Melly Mel’s rose to become a household name in Madison for its southern home-cooking menu and city-known catchphrase, “Where’s ya’ mama at?” Yet, even with its popularity, inconsistent employees, and the hidden costs of rent, insurance, supplies and other bills proved challenging. The restaurant’s revenue was just enough to keep going for five years, but Jackson closed the restaurant in November 2015.

“Part of the reason I closed it was trusting employees,” Jackson said. “I didn’t have a manager; I did everything from the shopping to a lot of the cooking, the prep of all the food, the marketing, everything. It got to be very strenuous.”

“She went through outsiders and family members, with any spectrum of person under the sun there were hurdles with which required her to be there 60 to 70 hours per week,” added Jackson’s nephew Brandon.

Such labor conflicts fueled the closure of Melly Mell’s, but not Jackson’s zeal for creating culinary delights. Now as a full-time catering business, Jackson books jobs on her cell phone and rents out kitchen space as needed through a membership with Food Enterprise and Economic Development (FEED) Kitchens, a non-profit facility that provides five commercial kitchens available for rent by the hour with specialized equipment.

“When we closed, it was an uproar from the community, but it kicked off the catering business,” Jackson said. “It hasn’t slowed down at all: schools, weddings, car dealerships, and colleges. Just today, I got three calls for jobs.”

Like Anana, Jackson has no official staff, which reduces the cost of labor. She mostly employs family members.

Forgoing office costs and regular employee wages allows these two Madison entrepreneurs, like many other black business owners, an opportunity to pursue a career driven by passion rather than just paying the bills, in the process innovatively overcoming economic discriminations experienced by blacks in the state and nationwide.

On the other hand, sole proprietorship minimizes the expansion of black wealth and opportunity in the community, regardless of the cultural impacts or contributions they provide.

The “team of me” may serve as a stepping stone towards increasing the presence of black businesses; however, it does not mitigate the economical and structural attrition of many black entrepreneurs.

Correction: A previous version of this story stated that UMOJA was founded in 1997.

|

|

|

Welcome to the Madison Commons, a website designed to provide news and information about all of Madison's neighborhoods and a crossroads for the discussion of community issues. The name comes from the idea of a village commons, a place for news, talk, debate, and some entertainment, too, that's open to everyone.

All rights reserved. Read more about the Madison Commons and its partners.