A fresh bluegill caught in Lake Monona. The state recommends women of childbearing years and children under 15 eat it at most once a week (Yilang Peng/Madison Commons)Fish from Madison’s lakes contain contaminants that can pose adverse health effects to people who consume them. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources has issued recommendations suggesting that people limit their consumption of fish caught in the lakes.

A fresh bluegill caught in Lake Monona. The state recommends women of childbearing years and children under 15 eat it at most once a week (Yilang Peng/Madison Commons)Fish from Madison’s lakes contain contaminants that can pose adverse health effects to people who consume them. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources has issued recommendations suggesting that people limit their consumption of fish caught in the lakes.

Yet those advisories may not be reaching everyone, especially low-income people and minority groups, who are more likely to eat fish from the city’s lakes. Moreover, programs to spread the word about the hazards of these fish have been limited or cut in response to limited resources.

“Given the hard economic times, I suspect more people than ever are fishing for food -- predominantly lower income and minority (people),” said Maria C. Powell, an environmental scientist and president of the advocacy group, Midwest Environmental Justice Organization (MEJO). This may be leading to disparities in contaminant exposure that may have long-term health consequences.

Mercury and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are two primary concerns in fish from Madison lakes, said Candy Schrank, an environmental toxicologist at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Overconsumption of these contaminants has been connected to immune deficiencies, reproductive dysfunction and problems in childhood development. The effects may only show in the long run or in the next generation, putting children and women of childbearing age at highest risks.

By measuring the concentration of contaminants in fillets from different areas and comparing them to values that keep the adverse effects minimal, the department put species from statewide waters into different meal categories, said Schrank. With increasing level of toxins, fish are classified as “one meal a week,” “one meal a month,” or even “don’t eat.”

General statewide guidelines apply to fish from most inland waters, which exclude the Great Lakes. They recommend that women of childbearing age, nursing mothers and those younger than 15 consume most panfishes -- like bluegill, crappies and yellow perch-- at most one meal per week. Sport fish like walleye and pike are in the one-meal-per-month category. Musky, a long-lived predator that can accumulate a high level of contaminant by eating other fish, is put in the “do not eat” category.

For“women beyond their child-bearing age and men,” the recommendation is less restrictive.

Fish advisories may vary across different water bodies. View the map to find out guidelines given for Madison’s lakes]

Madison’s lakes have a higher level of PCBs, a chemical that tends to accumulate in fish’s fat. Therefore, the DNR issued more stringent advice on consuming carp, a particularly fatty species, from Lakes Mendota, Wingra and Monona.

“We have been working on fish consumption advisories since the 1970s, so it’s a long-term, continuous effort,” Schrank said.

The department has included health advisories in the fishing regulation booklets, which are issued to anglers when they buy fishing licenses. It has a website on the topic, where information is translated into Spanish and Hmong. It distributes information through email and Twitter. It even posted a video on YouTube.

In Powell’s view, however, these methods hardly reach the poor and people in minority communities. They are people who, in Powell’s words, “don’t have computers, or don’t go online,” and yet often consume more fish than what the advisories recommend.

For instance, teenagers in Hmong community go online, “But their parents won’t, their grandparents won’t, and they are still out there, and they are the ones who are fishing more,” Powell said.

A major barrier in reaching minority groups, said Powell, is the “institutional racism” within government agencies.

“They make assumptions about what people do, how they eat, and how they understand things based on western European white culture,” Powell said. “What they don’t do is realize that not everybody is like that, not everybody thinks the same way, or talks the same way.”

Debate continues over how well warnings are reaching the fishing community.

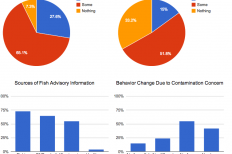

In 2011 and 2012, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and the Wisconsin Division of Public Health found that nearly all Wisconsin male anglers older than 50 had at least heard of advisories for mercury, though only two-thirds had some knowledge about PCBs. Respondents said they got their information about fish safety primarily through fishing regulation guides and the DNR website or publications.

A Wisconsin DNR and Division of Public Health survey showed, most anglers knew of mercury advisories and many of them knew about PCBs. Government issued materials were their major information sources.

A Wisconsin DNR and Division of Public Health survey showed, most anglers knew of mercury advisories and many of them knew about PCBs. Government issued materials were their major information sources.

But as the report noted, the survey sample had higher than average education and income, and was primarily white. The majority in the sample - 94 percent - hold a current fishing license. The survey was distributed online, which required participants to have access to the Internet.

“Most people we are talking about either don’t have [licenses], or they don’t participate in the surveys,” Powell said.

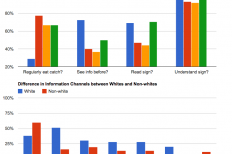

In the spring of 2009, at the request of MEJO, 22 fish consumption advisory signs were installed at popular fishing locations around Madison waters. That summer, Public Health Madison and Dane County and MEJO staff surveyed anglers at these spots to evaluate the effectiveness of signs. A survey following the installation of signs showed a clear gap among different racial groups regarding their awareness of fish consumption advisories, and attention to signs and advisories in mass media.

A survey following the installation of signs showed a clear gap among different racial groups regarding their awareness of fish consumption advisories, and attention to signs and advisories in mass media.

It turned out around half of the anglers interviewed read the signs and almost all of them understood the advisories, wrote Jeffery Lafferty in e-mail, an environmental epidemiologist at Public Health Madison and Dane County.

But the signs were not effectively reaching anglers at the highest risk, said Lafferty. The majority of white and Hispanic respondents read the signs, while less than half of African Americans and Hmong did.

The results showed a clear gap between whites and other minority groups. In the survey, 74 percent of non-white anglers consumed their catch regularly, while only 29 percent of whites did that. By contrast, only 39 percent of non-white interviewees had encountered similar information before, while 73 percentof whites had prior knowledge.

The survey also revealed that groups acquired information differently. Among those who had seen advisories before, non-white participants relied less on mass media, like newspapers, television, and the Internet than white participants.

“Communication was a huge issue,” Powell said. Based on her experiences dealing with minority and low-income communities, she concluded the most effective outreach is “in-person,” which means going to shorelines and community centers, getting translations, and building trust and relationships.

“Unless you have a lot of boots on the ground, people walking and talking to people, you are not going to be able to contact everybody,” Schrank said. “If you want to reach one hundred percent, then you have to know one hundred percent all the time how everybody gets their information. That’s what we don’t know.”

Feltoe Handley often catches bluegill and crappies to eat with family. He knows some lakes have mercury, but said he would expect a sign to be posted if the fish were not safe to eat (Yilang Peng/Madison Commons)The sign program has no follow-up.

Feltoe Handley often catches bluegill and crappies to eat with family. He knows some lakes have mercury, but said he would expect a sign to be posted if the fish were not safe to eat (Yilang Peng/Madison Commons)The sign program has no follow-up.

Powell wrote in an email that her organization had asked for years to place more of them around the lakes and get missing signs reinstalled. Eight signs in total were missing at popular fishing spots. However, the requests were often dismissed by public health agencies, despite what Powell considers a relatively low cost for the signs.

“It was just a one-time thing,” Lafferty said. Limited funding was provided for this particular project, and was not continued. With a lot of programs going on, the Public Health doesn’t have the resources, he said.

In the last few years, the department has received very few calls about mercury poisoning .

“I’m not saying that they are not out there,” said Lafferty. “It’s usually the people who don’t follow the guideline. They over consume the fish.” Leroy Martin travels to different areas to fish. He said he followed the DNR reports on mercury levels closely, but did not think that others did the same (Yilang Peng/Madison Commons)

Leroy Martin travels to different areas to fish. He said he followed the DNR reports on mercury levels closely, but did not think that others did the same (Yilang Peng/Madison Commons)

“We don’t believe that signs are the answer,” Schrank of the Department of Natural Resources said, given the sheer number of rivers and lakes. Statewide, DNR installs signs at three heavily polluted locations where no one should eat fish there. But even those signs are difficult to maintain.

“If you put a sign here, people are going to fish there.” She recalled a case where someone from Milwaukee saw signs along Madison lakes and decided to go back to fish in the Milwaukee area, which was more polluted at that time.

Yet informing people is only the first step; making people change their behaviors is the next. As the DNR survey revealed, 44 percent of respondents chose to change nothing after learning about contaminants from fish. The most common way of modifying behavior was to eat fish from different locations, not eat less fish.

Some anglers had six or seven kids but not very much money, Powell said, it seemed almost unethical to tell them not to eat too much fish if they needed to. But they should have the information to be able to choose whether they were willing to take that risk.

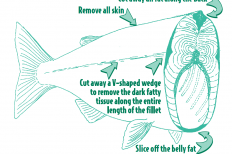

And there are ways to lessen exposure to contaminants, Powell said. People can remove the fat to reduce PCBs, and eat smaller fish or less contaminated species. Women can also modify their diet while they are pregnant.

The Wisconsin DNR advises people to remove all skin and fat in fish, and cook properly to reduce intake of chemicals (Image courtesy of Wisconsin DNR).

The Wisconsin DNR advises people to remove all skin and fat in fish, and cook properly to reduce intake of chemicals (Image courtesy of Wisconsin DNR).

For now, MEJO has turned its attention to other issues.

“Race and class disparities in fish consumption are not priorities for our government agencies here,” Powell wrote in e-mail. “This makes our efforts to address these issues very challenging -- and often totally futile.”

Often, it felt like “beating your head against a brick wall,” she said.

|

|

|

Welcome to the Madison Commons, a website designed to provide news and information about all of Madison's neighborhoods and a crossroads for the discussion of community issues. The name comes from the idea of a village commons, a place for news, talk, debate, and some entertainment, too, that's open to everyone.

All rights reserved. Read more about the Madison Commons and its partners.

Comments

Fish advisories

I fish and know you can catch bigger gamefish from shore, not just from boats, so people really should be careful about how many big fish they

eat.

The whole fish advisory thing is a joke. The DNR makes millions of dollars from fishing licenses and promoting fishing, they won’t do anything to jeopardize that. I get my license every year at one of several bait and tackle stores I go to and they NEVER give you a fish advisory booklet.