UW–Madison senior Rhia Dhingra is one of the many Madison residents currently living in a building that won’t be here this time next year.

Like many other downtown residents, Dhingra has struggled to find housing within her budget and has competed for the seemingly few units that fit her price range.

Due to the ticking clock on the life of her apartment building, Dhingra knows that certain things in her unit will go unfixed because it’s being torn down so soon. When her cabinets became completely soaked through from a burst pipe, she contacted the maintenance team in her building to fix the problem.

“During our conversation, he mentioned that anything major affecting the way you live will get fixed, but it’s the last year of this building, so it’s not worth fixing everything,” Dhingra said.

When you combine this with the maneuvering around construction projects, Madison can be a difficult place to live at times. An epidemic of construction has seemingly taken over the city , with a constant flow of various houses, apartments and businesses being torn down to make room for the influx of new residents. With this comes higher rent, as newer buildings with more amenities are built.

“I don’t think the answer is that we should do construction elsewhere because it’s an inconvenience. It's kind of just frustrating, I think because they're building all these buildings and I really can’t afford it,” Dhingra said. “I’m in a very privileged position where I am not stressing about rent. That being said, I don’t think what I'm being charged for rent is practical or a fair assessment of the living conditions.”

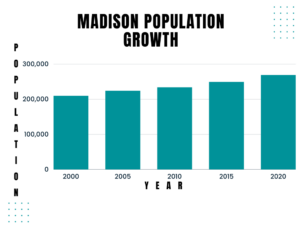

Madison has grown by roughly 60,000 people since the year 2000, which marks a 22% increase in population in the last 23 years. For the last couple of years, the city has been growing pretty steadily at 1.5% per year. As a result, there has been a boom in construction, with preexisting residences being torn down to make room for apartment buildings with more units that can accommodate the population growth.

To many citizens, community members and visitors, it may feel like every which way you turn there is construction. According to Kurt Paulsen, urban development professor at UW–Madison, this mass change and development is much more complicated than what meets the eye.

“Every year we have underproduced housing relative to the growth in households of people moving here,” Paulsen said. “So even though everybody looks around, and they see a lot of stuff being built, the trend in vacancy rates of housing has gone down.”

Due to Madison’s steady growth, this isn’t the first time the city has seen this level of change.

“So what you’re probably missing is you’re seeing all the new luxury construction downtown that is moving out of small houses, but what you don't see is, of course, what happened 20 years ago — the same thing,” Paulsen said.

As Paulsen states, this rapid expansion is the result of a few things. Madison is a city that draws from a variety of demographics. The city houses a large state university and a booming tech industry, with large employers such as Epic. Madison is also home to the state Capitol and must house government workers and their families. All of this occurs on an isthmus, with not much geographic space to expand. Paulsen said the solution is to build up, but not higher than the state Capitol, because there are height restrictions in Madison that must preserve the view of the building.

This, of course, doesn’t include the option of living farther out and commuting into town every day, which Paulsen notes would only add to the traffic congestion. With so very little space in the popular downtown area, the solution is to build as much housing as possible as high as possible.

“As long as we’re going to have lots of students who want to live close to campus, we just need to build lots of housing to absorb that demand,” Paulsen said. “And the university can't build it because they can’t build any more dorms. So it’s going to have to be the private sector. And they need to charge enough to cover their cost, which means they need to go towards the top of the market.”

In a city with a rapidly growing population, it’s obvious that apartment living is more practical, but there needs to be an effort made for parks and recreation areas to really prioritize the quality of life, according to Harry Bennett, a board member of the Regent Street Co-Op.

“We need to compress into smaller dwellings that are more efficient,” Bennett said. “You can have more of them in a city proper.”

An increasing population comes with more issues than just housing, and in Madison, traffic congestion is only getting worse with time. It’s also important to consider alternative forms of transportation for the city's population.

Bennett’s main form of transportation is biking. He believes if the streets were better equipped for bikers, more people could live farther away and not add too much to the traffic congestion.

“I’ve been trying to prove it since I moved here,” Bennett said. “You can bike five miles, two times a day. Every single day. There’ll be some days where it really sucks, and I’m 74 years old. I can do it.”

The city is predicting that by 2050, Madison will have grown by 115,000 residents. With another impending population spike, and a need for more affordable housing, who knows where the city will go next.

“I, as a professional planner, have a good solution. But it’s not popular. The solution is Regent Street, low-density, tall buildings,” Paulsen said. “Keep the retail and restaurants and the bars and the kind of street-life stores, but build housing above it. You could absorb a lot of that student housing demand.”