In February 2017, Torrie Kopp Mueller visited Grace Episcopal Church in downtown Madison — well, at least the basement of it.

Mueller had just been appointed the City of Madison’s continuum of care coordinator under the Homeless Services Consortium of Dane County, and she was eager to see the state of the city’s men’s shelter, which, at the time, was set up in three church basements.

At the sight of the dark, cramped setup, her excitement quickly turned to disappointment.

“Right away, I thought, we have to do better for people,” Mueller said.

With roots linking back to the 2008 recession, Madison and Dane County have struggled with the effects of an affordable housing crisis that has significantly worsened homelessness in the area. The city is working on multiple new shelters and low-income housing initiatives that are set to open their doors in 2024.

According to Kurt Paulsen, a professor of urban planning at the UW–Madison, while the city of Milwaukee has a higher poverty rate, the city of Madison has a notably higher homelessness rate.

“We actually know that it’s not poverty, substance abuse or mental health, but the lack of affordable housing that’s the cause of homelessness in Madison,” Paulsen said.

The basis of Madison’s affordable housing crisis can be attributed to its extremely low vacancy rates. When vacancy rates are low, the market power falls into the hands of the landlords. According to Paulsen, a healthy vacancy rate is anywhere between 5% to 10%; the city of Madison’s vacancy rate has been an average of 2% since 2019. Such a competitive market means landlords can afford to be picky about who they rent to, and that they often rule out people experiencing homelessness.

Another struggle stems from the city’s low units to households ratio. Between 2006 and 2022, Dane County added 65,000 households, but only 53,000 housing units.

“It’s not rocket science, it’s basic math,” Paulsen said.

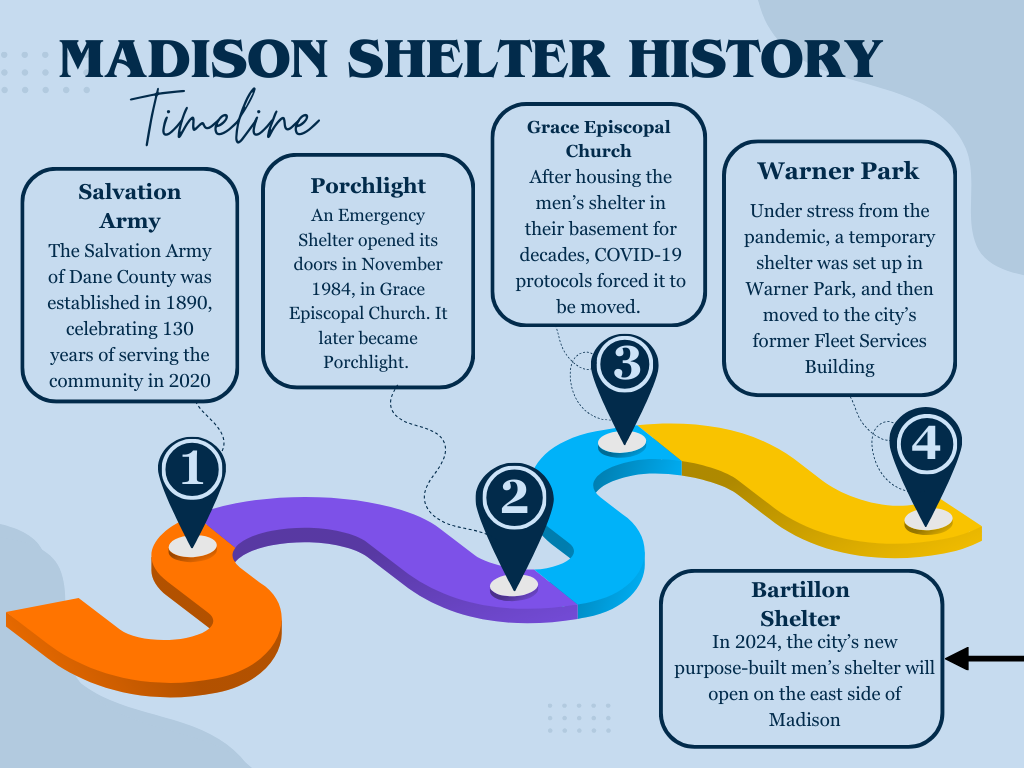

Though the city has worked to attack the issue with several housing initiatives in recent years, they have not catered towards the homeless population. For years, church basements were the best the city had to offer — until March 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a wake-up call. A combination of growing demand and limited space for social distancing forced city officials to pivot away from Grace Episcopal Church and set up an emergency shelter in Warner Park.

“It became clear that a permanent shelter needed to happen,” Mueller said.

Two years later, Mueller’s cries were finally heard. In 2022, the city and county announced long-awaited plans for the construction of a permanent men’s shelter on Madison’s east side, in collaboration with local homeless services nonprofit Porchlight. This shelter will be the first of its kind in Madison. Located on Bartillon Drive near the Dane County Regional Airport, it will operate 24 hours a day and offer intensive wraparound services like transportation and job training for its guests.

Porchlight has largely collaborated with the city throughout the planning process and is set to fully operate the shelter upon its opening.

“We’re calling it a purpose-built shelter,” said Karla Thennes, executive director of Porchlight. “We’re designing it for exactly what we need.”

Expected to open to the public in 2025, the Bartillon shelter will boast amenities like a kitchen, backup generator and additional space for daytime programming. It’s not the only shelter initiative in the works, though.

The Salvation Army of Dane County received a $4 million federal grant for a new shelter for women and families in March.

The new campus, set to open next year, will include two buildings on East Washington Avenue — a temporary shelter and an apartment building meant for longer-term housing. The facility will have resources like a medical respite center and a community center.

The shelter will provide space for 42 families and 82 single women, and the apartment building — The Shield — will include 44 units.

Both the Bartillon shelter and the Salvation Army shelter will be vital resources for addressing the local homelessness crisis, but in reality, they will only scratch the surface of a problem that has much deeper roots. A combined recent influx of residents and a steadily increasing population projection for the coming decades means the affordable housing crisis is likely to only worsen with time.

While new shelter initiatives are beneficial, they are hardly a long-term solution, Paulsen said.

“It’s like triage, or stopping the bleeding,” Paulsen said. “As soon as these shelters are built, the next thing we need to do is turn around and build some more.”