In an effort to avoid a spike in COVID-19 cases on campus and throughout the surrounding community like that seen last fall, the University of Wisconsin-Madison instituted a new, more rigorous saliva-based COVID-19 testing regimen this semester, creating a difficult transition for students returning to campus.

Undergraduate students living in the Madison area are now required to get tested for COVID-19 twice a week, regardless of how many in-person classes they have. The new testing protocols are based on those instituted at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, which has required its students to get tested twice weekly since last semester.

This is a major departure from the University of Wisconsin’s testing requirements in the fall, which only required COVID testing for students living in residence halls. Now, all students living in the zip codes 53703, 53705, 53706, 53711, 53713, 53715, 53726 and 53792 are included in the university’s twice weekly testing requirements, according to the COVID-19 response website.

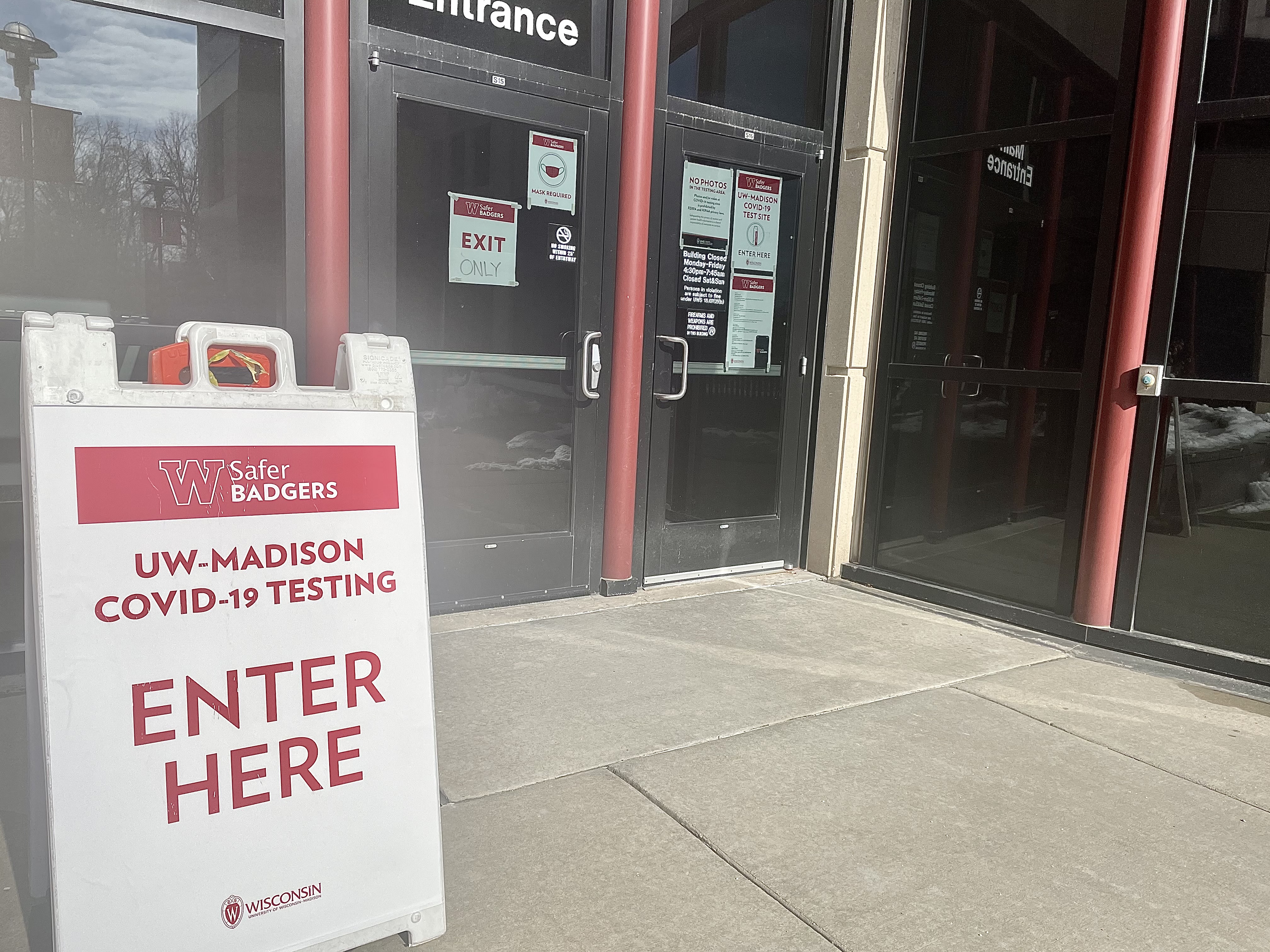

Another main feature of the new testing program is the Safer Badgers app, which students can use on their smartphones to check wait times at testing sites, receive test results, submit symptoms of COVID-19, and produce their Badger Badge, which they must present in order to enter campus buildings starting February 10. The Badger Badge will turn green, allowing building access, if individuals are in compliance with testing requirements, have not reported any COVID-19 symptoms and are not required to be in quarantine or isolation.

In the early weeks of the new testing regimen, only about one half of one percent of tests have turned up positive results.

Keeping up with the tests

Krista Nagel, a senior undergraduate at UW-Madison, said she thinks increased testing is a smart idea. However, Nagel said getting tested twice a week seems like “overkill,” and she feels that weekly testing would be sufficient.

Unlike undergraduates, graduate students, faculty and staff on campus are only required to get tested once a week. University spokesperson Meredith McGlone said the reasoning behind this is that there are different factors to consider for the undergraduate population, like the prevalence of COVID-19 in their age group. McGlone also pointed to the university’s use of twice-weekly testing for undergraduates living in the residence halls last semester.

In the fall, a major spike in the number of COVID cases led the university to pause all in-person instruction and quarantine all residents in Sellery and Witte Residence Halls for two weeks. As a result, students living in residence halls were tested on a more consistent basis, including as often as twice a week after they returned from Thanksgiving break.

“What we learned from last fall is that the more frequent testing and the regular testing that we have, and the more comprehensive that it is, the more likely that we’ll identify cases that are developing more quickly,” said Jake Baggott, Assistant Vice Chancellor and Executive Director of University Health Services, in a media briefing on January 21.

While students living in residence halls are still tested using nasal swabs, the rest of the university population has been switched to saliva-based testing. McGlone said the reasoning behind this is that the nasal swab test, which is processed by the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, allows for a capacity of about 12,000 tests per week. The Shield T3 saliva-based tests add up to 70,000 additional tests per week.

“Pool your drool”

One major learning curve with saliva-based testing is educating the university community on how to properly collect a saliva sample. The Office of the Chancellor released tips in mid-January on how to avoid getting a rejected saliva test, advising individuals to “pool your drool under your tongue,” among other tips like stimulating your salivary glands. However, rejected tests continue to persist among students.

Nagel is one such student. Her second saliva-based test was rejected despite the staff at the testing site approving her sample. She said she was never told why her test was rejected, but called her experience with saliva-based testing “awkward” and “gross.”

Alex Lafferty, a freshman at UW, said getting his first test rejected was “a little bit frustrating.”

“They gave us all of these guidelines to do in order to not get a rejected test, and I followed all those and I still got a rejected test,” Lafferty said.

In a media briefing on January 21, Baggott said there were “a number of rejections early on in the process,” though he didn’t specify how many.

Saliva-based testing differs from nasal swab testing in that individuals are asked to refrain from eating, drinking, brushing or flossing their teeth, chewing gum or smoking for the hour before they test.

Nagel said this makes the testing process inconvenient, adding, “I miss the nose swabs, they were so much easier.”

Lafferty, who lives in an off-campus apartment, said that testing is much different for his friends living in residence halls, since they’re continuing to use nasal swab tests.

“I envy them a little bit, just because I’d much rather do a nasal swab than the new saliva test,” Lafferty said.

The possibility of a rejected saliva test worries Lafferty, because he needs to receive his test results in order to enter campus buildings for in-person classes.

“What if I get a rejected test and I’m denied from the building because I don’t have the green Badger Badge?” Lafferty said. “For me personally, that causes a little bit of anxiety.”

Relieving anxiety about testing compliance is why the university has delayed enforcement of the Badger Badge several times, McGlone said. Though building access restrictions were originally supposed to begin at the start of classes on January 25, the start date was shifted to February 1, then to February 8, and most recently to February 10.

“Given the challenges that we’ve been having with the wait times and particularly the turnaround times on testing, we felt like extending the date ... would hopefully decrease some of that anxiety, [and] give people more time to come into compliance,” McGlone said when asked why the start date was shifted.

In their most recent communication, the university gave slightly different rationale for why they changed the enforcement start date to February 10. In anticipation of increased testing demand leading up to Monday, February 8, the university said they wanted individuals to “be able to leverage the additional test sites and hours that are available on weekdays as compared to the weekend.”

The Waiting Game

Waiting to get tested and waiting for results are additional challenges with the new testing regimen. Originally, individuals could schedule appointments to get tested, choosing from four appointment blocks per hour in 15-minute increments. However, the university switched to drop-in testing only beginning January 24, which McGlone said was done to reduce wait times.

“We came to see that [appointments were] actually contributing to some delays rather than minimizing delays because if you showed up a little bit early, for example, you would have to wait for your time slot to hit to be tested,” McGlone said.

Nagel said that her first time using drop-in testing, she arrived at a testing site with a very long line, and debated whether to wait or go somewhere else, eventually deciding to wait in line. She called the new drop-in system “a burden,” and said it made things more difficult if you’re trying to plan out your week or get tested in between classes.

Lafferty said he witnessed what looked “like a Six Flags line” for testing at Union South on January 24. Yet, he said he also had a positive experience with drop-in testing when he was able to get tested at the Business School without planning it, since he was already there and the wait time was short.

McGlone explained that the Safer Badgers App uses color-coding to show how long the wait times are for open sites across campus, which she said allows for more convenience. With appointments, McGlone said individuals were “locked in at a certain site at a certain time,” which restricted flexibility to visit other sites with shorter wait times.

With thousands of tests processed per week, the wait time to receive results has been longer than anticipated. University guidance originally said results would be ready within 24 hours, but students have reported waiting several days for results.

At the time of his interview, Lafferty said that none of his test results were returned within 24 hours, but he did receive them all within 48 hours.

According to recent communication, the university recognizes this issue and is adding more staff to try and achieve a 24-hour turnaround time as soon as possible.

Hopes for a Smooth Semester

In a media briefing on January 21, Dr. Lori Reesor, Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs, said that saliva-based testing is “a whole new socialization process,” and that the university is asking “for people’s patience and grace” as they begin this process.

McGlone emphasized that testing “is just one element of the strategy,” and said it’s imperative that students continue to wear face coverings, social distance, avoid gatherings with people outside their household, and wash their hands frequently.

Lafferty said that students want to be compliant, but the constant changes make it hard to keep up.

“All of the students want to abide by the rules that the university puts in place,” Lafferty said. “But it’s sometimes hard to follow those rules because they’re ever-changing.”