This story is part of a two-year (2024-26) series prioritizing solutions to housing insecurity through collaborative storytelling. For more information about the series, please see the project overview. For questions or comments, please contact Sue Robinson at robinson4@wisc.edu.

Earlier urban renewal initiatives continue to haunt Madison, but housing developments like Bayview show us how we can learn from those mistakes.

Last fall, Chapter, a 10-story apartment building, opened just a few blocks south of the UW–Madison campus. To make room for Chapter’s construction, five buildings were demolished, including Buckingham’s Bar & Grill, which stood on Regent St. for nearly 100 years, one of the last few remaining buildings that had been part of the original Greenbush neighborhood.

Before it was Buckingham’s, the now-demolished structure was the DiSalvo grocery store, a reflection of the once vibrant and diverse Greenbush neighborhood, which, from the late 19th century and the 20th century, was, inhabited primarily by Italian Immigrants, Jewish people and people of color.

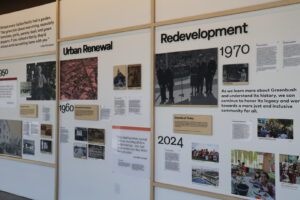

To honor this history, Chapter implemented a gallery of photos and informational plaques to acknowledge the now-extinct version of the neighborhood.

But the original demise of the Greenbush began long before Chapter.

After the stock market crash of 1929, the Great Depression and the Second World War, American cities were in desperate need of new development, with much of the American housing stock devoid of heat, electricity and adequate space, according to UW–Madison professor of urban planning Kurt Paulsen.

In response to overcrowded housing and less than comfortable conditions, a new federal government effort was born: urban renewal. Lasting from 1945 until the mid 1970’s, urban renewal sought to update and beautify American neighborhoods, according to Paulsen.

“The main component of urban renewal was federal money to acquire larger chunks of older urban neighborhoods, knock down the decrepit old housing that was there and replace it with newer, more modern housing,” Paulsen said.

At first glance, the work of urban renewal seems commendable—updating American housing to make conditions more suitable for the families who lived there. But, as Paulsen explained, there were three major problems with the effort.

First, there was a lack of public participation in the project; urban renewal failed to involve any residents in the planning processes, and they would subsequently be negatively affected by the redevelopment plans, according to Paulsen.

“Today, you would never do anything even close to that. You would have 10 years of public meetings and lawsuits, and a lot of that framework is a response to the problems of urban renewal,” Paulsen said.

Second, urban renewal’s housing development projects resulted in social destruction—disruptions to people’s longstanding daily lives and routines.

“Modernism believed that tall buildings and super highways and efficient buildings made life better for people,” Paulsen said. “But really, it made the cities worse, whether it’s freeways that separated neighborhoods or the deliberate isolation” of the public housing complexes that were sited away from the networks and communities helped define their residents’ cultural identities.

The third and biggest problem with urban renewal’s housing developments, according to contemporary critics, is that they disproportionately affected immigrants and people of color—pricing them out of their neighborhoods, and separating them from their communities. In Madison, that meant that the Triangle—part of the famously Italian working-class Greenbush neighborhood bordered by Regent, Washington and Park streets—was a target of the program, according to Pauslen.

Mary Berryman Agard is the board chair at the Bayview Foundation, a nonprofit organization that provides housing and community services for low-income Madisonians in the Triangle.

“Greenbush was an impoverished neighborhood, but a very vital and healthy and highly connected and integrated neighborhood, principally of Italian and Jewish and Black residents,” Agard said.

Nevertheless, The Triangle Redevelopment Plan, created by the local government and supported by federal dollars in the early 1960s, resulted in 233 residential and 33 commercial and industrial buildings being razed to make way for a hospital expansion and new housing developments—and in the process, many of the demolished lots sat vacant for years. Ultimately, the Triangle Project forced over 1,150 people out of their homes, effectively erasing the vibrant community that once defined the area, according to the Community Development Authority, or CDA, a body that works in conjunction with the City of Madison to create and manage low-income housing..

“When urban renewal came along, residents were bought out if they had property, or in a few cases, condemned out. If they were bought out, subsequent research has shown that they were given very devalued prices for their property” that left those who were property owners “in a disadvantaged position with regard to securing subsequent housing,” Agard said.

Community members took notice of the injustice and the ensuing struggles residents faced as a result of urban renewal’s aggressive approach to demolition and relocation, according to Agard.

“There was a group of leaders in the community who were aware of the way in which those residents had been unhoused and disadvantaged,” Agard said, “and they got tired of waiting for the city to do something.”

So instead of waiting, these community leaders got to work. In 1966, they formed the Bayview Foundation and scraped together money to finance a low-income housing project, with its former president and one of the original founders, Judge Paul Gartzke, even putting his home up as equity in order to secure a bridge loan to create the original 102 units of affordable housing. Soon after its inception, Bayview’s first community center started in one of the apartments—a way to carry on a sense of mutual support that made the original Greenbush neighborhood so dear to its residents, according to Agard.

Much of the housing that was constructed as a part of the Triangle Redevelopment program still stands today, in varying states of deterioration. And the CDA has devised a plan to reimagine the Triangle site “into a thriving urban, sustainable community that fosters health, wellness and connections among residents and the larger community,” according to the CDA and it’s partner on the project, New Year Investments.

The project will begin its reconstruction of the Gay Braxton, Brittingham apartments on Braxton Place, and Parkside and Karabis apartments on South Park Street this spring, according to a winter 2025 newsletter.

How urban renewal persists today

Although government-funded urban renewal efforts ended in the mid-’70s the concept of urban renewal still exists in Madison today, according to Paulsen.

“Think of the older neighborhoods like Mifflin Street or East Johnson Street, where you have a lot of 1920s/1930s kind of rundown housing. Developers are buying a few parcels—smaller houses, older houses—to consolidate them into one, knock them down and then build a taller building. That’s private-led urban renewal,” Paulsen said.

In fact, CRG, the same developer that demanded the removal of a historic Greenbush building for the Chapter apartments, was looking last summer to construct a second apartment complex on West Washington Avenue and Mifflin Street that would have required the demolition of smaller (and, likely, more affordable) residences, according to a July 2024 project application sent by the developer to the City of Madison’s Urban Design Commission.

Although Mifflin Chapter hasn’t yet come to fruition, just down the street from its proposed location, a six-story, 140-unit apartment building on West Washington Avenue recently replaced nine multi-family residences. Renting a studio apartment in the new complex, Virtue, slated to open this summer, will cost $1,750 per month.

This private-led urban renewal is causing concerns with the city council, according to Paulsen, because in most cases, residents are displaced, and the new and proposed housing projects have higher rents than older properties.

But amid this modern wave of urban renewal, Bayview continues to serve Madison’s low-income populations, offering more services than ever, including youth, adult and senior programming, as well as a food pantry—keeping the community at the heart of the foundation.

And more than just improving their social services, in December 2024, Bayview finished a redevelopment project, adding 30 new units—almost doubling the number of residents served. While planning the project, Bayview staff were influenced by the missteps of the earlier wave of urban renewal and wanted to involve their residents in the redesign, according to Agard.

First, they ensured public participation, surveying residents and including them in planning meetings.

“We folded our residents very specifically into setting the standards for the redevelopment. We surveyed 70% of residents, and we had meetings in three languages” to make sure everyone was “asked what they wanted, and whether the architectural plans really gave them what they wanted and what they would suggest,” Agard said.

Second, they kept community togetherness in mind when considering the architecture of the redevelopment.

“We had an architectural firm that was interested in building communities, not just buildings,” Agard said.

And third, Bayview staff vowed that they would not displace any residents during the redevelopment.

“We made a commitment to them that every single person who was living at Bayview would still be living at Bayview when the new buildings were built, as long as their eligibility to be there was the same. And furthermore, during the construction period we did not locate anyone off the property,” Agard said.

As a lack of affordable housing continues to be a problem in and around the city of Madison, Bayview is inspiring other community-oriented subsidized housing projects. According to Agard, they’ve had interest from places like the City of Sun Prairie, where city planners have expressed interest in wanting to learn how they could try to replicate the model in their area.

“What we engaged in was the razing and rebuilding of someone’s neighborhood, and that’s not very different from urban renewal,” Agard continued. “But, because our point of view from the start was that that had to be done in service to the residents, it becomes relevant to why we had more favorable outcomes than many other similar projects around.”