Tom Chang holds fond memories of his childhood.

He still recalls mornings where he would sit in the living room with his family, watching the television as the sun rose. He walked with his siblings to school and was often surrounded by fellow Hmong students in class, people he was always able to have a rapport with about anything Hmong: Hmong food, Hmong culture, movies dubbed in Hmong.

One day, he was taken out of class and told to complete an ESL test. After he passed, he started noticing that his friend’s schedules were different from his, and his peers were being placed in more ELL classes; they weren’t together as often. He says that it was at that moment he suffered from imposter syndrome, wanting to be around his friends and family in school, but placed with other students.

It was only in hindsight that Chang realized that school assessments were determining the educational environment he grew up in.

These were the memories of a young Hmong American in the city of Sheboygan.

A State of Diaspora

Wisconsin contains the third-highest Hmong (pronounced “muhng”) population in the United States, behind California and Minnesota, comprising 38% of the state’s Asian population.The Hmong people originally arrived in the United States from areas of Southeast Asia such as Laos, Thailand and Vietnam at the end of the Vietnam War. Nearly 50 years later, Hmong individuals carry that legacy and have been working to strengthen their community ever since.

When Chang came back home after graduating from college, he desired to work through his gap year before graduate studies. Wanting to interact with students, he applied for a job as an education assistant at a nearby middle school.

Within the education system, Chang acted as a medium between parents and the school, translating permission slips, explaining events — anything that required him to use his knowledge of the Hmong language.

For Chang, though, it was more than a matter of words.

“I was just hoping I could be a positive male role model,” Chang said. “Someone they could be comfortable with.”

He had to navigate the intricacies of the Hmong language, in which an idea that in English could be stated in one word, such as “program,” needed to be elaborated on and dissected.

“It is very poetic. It is based on metaphor, simile and hyperbole, all these other mechanics of what language offers us,” Chang said. “We don’t often talk at things, but we all talk around things.”

He recalls the challenges he faced when he was required to explain hockey to the parents of his middle schoolers. The intricacies of the game, the goals of it, even explaining the concept of a puck, could bring its own share of difficulties.

By his own admission, Hmong history is sometimes not well documented, a result of the absence of a standardized written language for hundreds of years. Despite this, there is a rich history behind not only the Hmong people, but their supportive role in U.S. foreign affairs in the latter half of the 20th century.

A History of Conflict

The Hmong people resided in areas of Vietnam, Laos and Thailand, and had a long history of migration within these places before the 20th century. But it was during the Vietnam War that the U.S. enlisted the help of the Hmong, and one of their greatest contributions was cutting off the supply line through the Ho Chi Minh trail. Their involvement against Communist forces would eventually come to be known to the Hmong as the “Secret War,” also known as the Laotian Civil War. These were the battles that Tom’s grandfather fought.

When the Vietnam War ended in 1975, the U.S. pulled its forces out of the area as the North Vietnamese Army invaded Saigon. America was left with the puzzling question of what to do about this group of people who had been their great allies in the conflict.

The U.S. would start relocating refugees, and the diaspora began.

The federal government sought to spread out Hmong refugees through its dispersal policy, attempting to ensure that the new residents would not all reside in California, where a large Asian American population already lived. The reasoning behind this was also to prevent the creation of Hmong enclaves in the U.S.

As Hmong refugees sought new homes in America, the Midwest, and Wisconsin in particular, emerged as one of the best places to establish new lives.

According to Alexander Hopp, a lecturer in Hmong American studies at UW–Madison, the reasons for this were mostly economic. In areas such as Wausau, Milwaukee and Sheboygan, the cost of living was lower. An education was not required, and these newcomers to the U.S. could work in industrial positions — positions that American residents didn’t want to fill.

It was in March 1993 that the Chang family relocated from Thailand to Sheboygan. The father of this clan had the opportunity to pursue an education, but instead entered the workforce immediately to provide for his family.

A year later, Tom Chang was born.

A Leap in Education

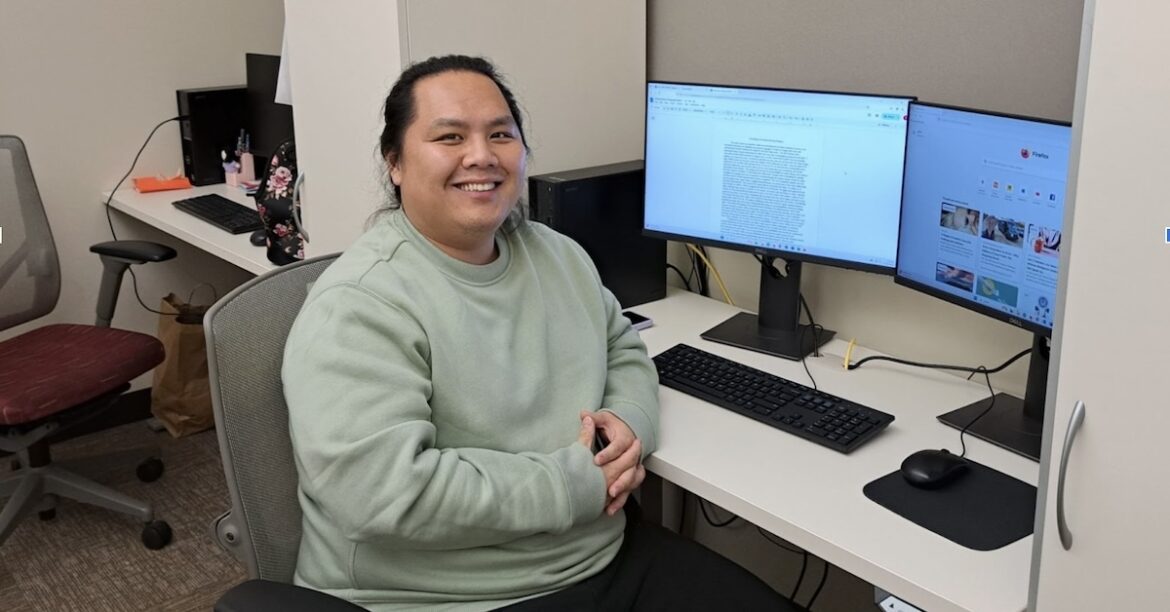

As a doctoral student 30 years later, Chang is a member of a research team led by UW–Madison Assistant Professor Maichou Lor that seeks to understand health changes for Hmong individuals over time. Chang hopes to provide better health care for Hmong individuals by helping create survey questions tailored to the Hmong language.

Besides the questions that need to be put on paper, there are also deeper ones at play.

“What does it mean to be aging out of place, aging without a home country?” Chang asks. “What sorts of illnesses may we be familiar with, and how do we understand dimensions of health?”

In his previous translation work, as well as his research now, Chang is part of a growing movement for Hmong representation in education. The UW system specifically has been a pioneering force in student representation, according to Hopp. With several of UW–Madison’s Hmong studies teachers on the track for tenure, the future of Hmong studies has a positive outlook ahead.

According to Larry Ashmun, a Hmong studies bibliographer at UW–Madison, the presence of Hmong people in education is increasing. “If you look around now, there are a lot of Hmong who are educated,” Ashmun said.

Over the past decade, the number of Hmong Wisconisinites who have attained a bachelor’s degree has not only increased by 6%, but the opportunities for teaching Hmong studies have expanded. In 2007, UW–Madison announced Hmong studies would be taught regularly; that same year, the university made Hmong language classes part of the curriculum.

This push for Hmong studies in recent years has come from a place of recognition for their past service, or the “politics of blood sacrifice,” as Hopp refers to it. Outside of the UW system, areas of ethnic studies such as Chicano or Black education often fail to come to fruition, but Hmong studies can be the exception.

“Hmong studies seems to have bipartisan support, because the people who would normally be against ethnic studies or conservative figures look at Hmong experience and say, ‘These are our allies in the Cold War, right? They deserve to be celebrated,’” Hopp said.

For Wisconsin, Hmong immigration remained a hot button issue for years, precisely because recompense was owed but not always delivered.

The issue would be further complicated with another wave of refugees arriving later on. In the mid 2000s, at the behest of the Thai government, Hmong refugees residing in Thailand were forced to leave a monastery known as Wat Tham Krabok. The U.S. sought to relocate almost 15,000 refugees, with some of that number going to Madison and Milwaukee.

It was this generation of Hmong children that Tom sought to reach, to ultimately work with as an educational assistant.

“We need a sense of community, to be able to be at peace, or to be able to be comfortable, or to be able to just have a place to belong,” Chang said. “And without that, I think we fall victim to this industrial system of education.”

Chang attempted to provide that community when he would talk with students. He would chat with them about food, family and music, and they could feel comfortable taking tests in his room. They knew that if they just went to room 243, they were allowed to be not just American, but Hmong American.

A Time of Remembrance

Recently, at a New Year’s Celebration, the Chang family reunited once again. Tom Chang’s grandfather wore his military garb, a memory of his service as a 15-year-old during the Secret War. Next year is the 50th anniversary of the end of that conflict, a time to remember past sacrifices.

May 14 is officially recognized as Hmong-Lao Veterans Day in Wisconsin, the last day Hmong families were evacuated out of Laos at the end of the Vietnam War. Despite this national recognition for Hmong Americans, those past sacrifices are not always commemorated as they should be.

Mai Zong Vue is the chief operating officer of the Hmong Institute, a nonprofit serving Hmong individuals and underserved communities in Wisconsin. For those like her who lived through the war, it can be painful to know that veterans of the Secret War can often be left out of receiving benefits due to their citizenship status, as well as their lack of recognition as soldiers during the Vietnam War.

“It’s really important to have time to reflect and think about why we’re here, the shoulders that we sit on,” Vue said. “It’s a time we can heal together, because there was so much lost during the Secret War.”

Most of Vue’s uncles lost their lives in those years, and her father ran away to Thailand soon after.

In Vue’s own work, she has sought to benefit communities in Wisconsin, including by co-founding the Hmong Language and Cultural Enrichment Program, which teaches Hmong language and culture to K-12 students in the greater Madison area. She has also worked in a health care capacity, providing mental health services and vaccinations, as well as food distribution during the COVID-19 pandemic when going outside presented dangers to the elderly. According to her, the organization has supplied more than 200,000 pounds of food to the community over the past 13 years.

Recent events like the International Festival, hosted by Madison’s Overture Center, offered an opportunity to celebrate Hmong culture and express their heritage.

“It gives them a reason to want and do more,” Vue said.“When people applauded and cheered, it gave them a sense of pride.”

It’s events like these that unite the Hmong people of Wisconsin from all areas of the state. As he hangs out next to the project office for Dr. Lor’s research program, Tom Chang thinks about his colleagues and, ultimately, the Hmong diaspora.

“Some of the students came to the U.S. in the mid 2000s from Thailand. Some are from Milwaukee, of course, I’m from Sheboygan. Some are Wisconsin Rapids, La Crosse, some are Madison natives as well,” Chang said.

After 50 years, despite spreading out to different corners of the state, Hmong people reunite over what they’ve lost, what they’ve accomplished and what can be gained in the future.

“And so we all triangulate through this spot, and just for the time being, we found ourselves here together.”