When Malorie Elmer was working as a mental health therapist in New York, she found the most common response to a mental health emergency was calling the police.

“The police just weren’t the right option for my community there,” Elmer said.

Now, Elmer is an embedded crisis worker in the Madison Police Department’s mental health unit, making it possible for the police to be the right option for those struggling with their mental health in Dane County.

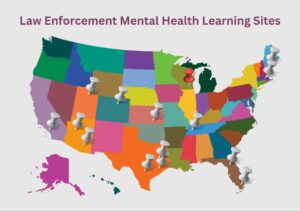

In 2010, the Council of State Governments Justice Center named the Madison Police Department a law enforcement mental health learning site. The department’s dedication to its mental health unit earned it the honor of becoming one of the inaugural programs in the nation, along with programs in five other jurisdictions.

Law enforcement mental health learning sites are considered a national resource for law enforcement and behavioral health agencies that are looking to tailor response models to suit their community's needs. In Madison, the police department saw a growing need for these models and decided to act on it.

In a collaboration with Journey Mental Health, the department now employs six full-time mental health officers — one for each of the city’s six police districts — and two in-house crisis workers, all of whom work together to respond to mental health crises in the Madison area. The team uses what it calls a hybrid model, relying on outreach and follow-up services with citizens, while also answering active calls as they occur.

Kenzie Cole, Madison Police Department’s West District mental health officer, worked in patrol for two years prior to shifting into her current role.

“Usually when you deal with a call in patrol, you respond and you’re done with it. You probably don’t think about it again, and you move onto the next thing,” Cole said. “There’s a different aspect I get in this role that I didn’t get in patrol. I can see things start to finish, which is really fulfilling.”

With their services, Madison Police and Journey Mental Health hope to combat preconceived notions about law enforcement, all while forging better relationships between police officers and the community. To date, the unit has created more than 500 police response plans for individuals in the community with persistent mental illness and cognitive disabilities.

“People experiencing some kind of mental health issue aren’t always welcoming to calling for help, or they’re weary of law enforcement in general,” Cole said. “When they do have a positive interaction with me in uniform, that can influence their perception. Maybe next time they’ll be more comfortable contacting the police when they do need help.”

The department started establishing a comprehensive criminal justice-behavioral health partnership with other law enforcement agencies and mental health organizations in the mid-1980s and it has been fostering these relationships ever since. One of its longest lasting collaborations is with the National Alliance of Mental Illness Dane County, which provides comprehensive mental health training for law enforcement and first responders.

Julia Hyatt, the National Alliance of Mental Illness’ programs and education manager, often facilitates the organization’s crisis intervention training and crisis partner training for Madison’s police and fire departments.

“Before [officers] are even out patrolling or doing their job, they’re getting mental health training,” Hyatt said. “They now have more positive interactions with their calls, they build relationships with members in their community, and they’re more comfortable.”

The National Alliance of Mental Illness’ involvement with the department helps to equip officers with the tools they need to safely and successfully assist people who are experiencing mental health crises. The two organizations have a continued relationship, with many Madison police officers returning for second or third trainings and applying what they’ve learned to real response calls.

One area of struggle for the mental health unit is expansion. The department is meant to have a third embedded crisis worker, but the position has been vacant for over a year, leaving the team with only eight people.

“It’s spread our resources thin. There’s not enough of us to give the attention we need,” Cole said.

According to Cole and Elmer, finding someone willing and suited for the role has proven difficult, especially because crisis work comes with a mental and emotional toll.

Dane County officials have also started to recognize the importance of mental health response within local institutions. In his 2024 budget proposal, County Executive Joe Parisi allocated more than $242 million for the safety net of social service work and programming, including a new $2.5 million grant program to aid local agencies and law enforcement with recruitment and retention of skilled providers.

Along with this, Parisi is also establishing a pilot team of crisis counselors that will be directly embedded into the county’s 911 center. With over $400,000 built into the budget for this program, the team will provide another layer of front line behavioral health support for the community.

“We have to work together. No one entity can deal with this on their own,” Parisi said. “[The pilot program] allows us to better deploy the in-person resources. If someone doesn’t need an in-person response, we can save that for someone who really does.”

Longer term, county officials are working on developing a crisis triage center, or, as Parisi puts it, a “no wrong door” location for anyone feeling in crisis.

With nearly 50 years of established practice, the Madison Police Department serves as a role model for jurisdictions everywhere. Following Madison’s example, hundreds of other police departments have invested in mental health units, implementing similar practices and response teams for their communities.

“It’s cool to see that there are a lot of other jurisdictions that are trying to do what we’re doing essentially,” Cole said.

Recognizing the need for mental health resources early on has set the Madison Police Department apart from the rest. Since the department was named a law enforcement mental health learning site 13 years ago, only nine other police departments have received the same honor, bringing the national total to 15.

Madison Police understands that sometimes it is inevitable for its officers to play a role in crisis response. With continued dedication to mental health education, it hopes to continue leading by example and trailblazing in this field for the sake of others.

“The systems are set up to where police need to be a part of the puzzle sometimes,” Elmer said. “We’re just trying to improve that when it happens.”