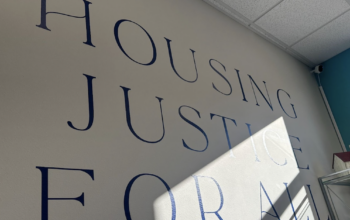

The Wisconsin Department of Corrections’ new policies prohibiting the donation of used publications to Wisconsin prisoners and to prison libraries took effect on Sept. 27 and Oct. 10 respectively, disrupting the efforts of Wisconsin Books to Prisoners, a Madison-based nonprofit.

On Aug. 16, the Wisconsin Department of Corrections barred the organization from sending used books to prisoners. According to an email that Sarah Cooper, an administrator in the department’s division of adult institutions, sent Wisconsin Books to Prisoners that day, the department made its decision to ban books from the organization as part of an effort to prevent drugs, including narcotics and other substances that can be sprayed onto paper, from entering prisons.

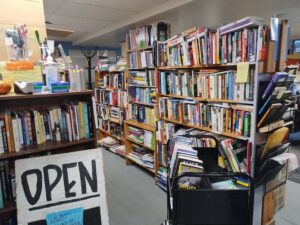

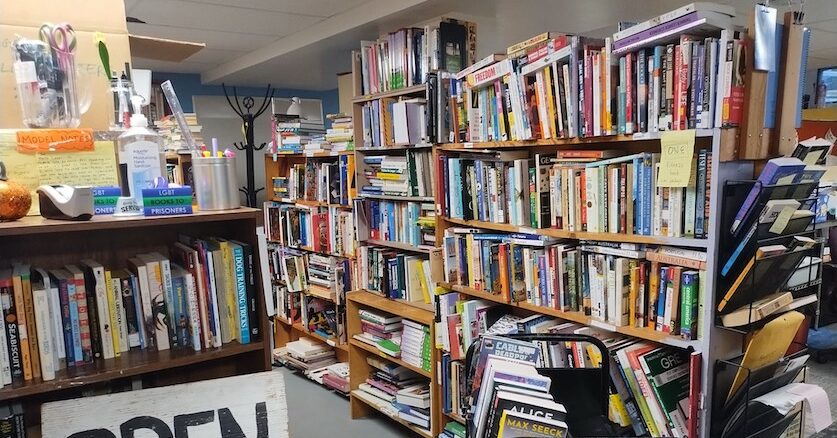

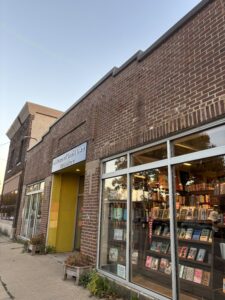

Established in 2006, Wisconsin Books To Prisoners is a volunteer-run nonprofit focused on sending requested and recommended reading materials to prisoners in Wisconsin. A project of the Madison bookstore A Room of One’s Own, Wisconsin Books To Prisoners works with local bookstores and community members to fill book requests from inquiring prisoners with deliveries of new and used books, according to its website.

“The announcement of Wisconsin Books to Prisoners’ recent bar came during Prison Banned Books Week, which is darkly fitting,” said Mira Braneck, a manager at A Room of One’s Own. “We at Room see this for what it is: an act of censorship. It is vital that people in prison have access to books.”

According to Cooper’s Aug. 16 email to Wisconsin Books To Prisoners, the department’s concern is over “the ongoing challenge of illicit substances coming into the prisons via the mail.”

Out of 881 drug-related incidents that occurred in state prisons from 2019 to 2024, 214 involved drugs being brought in on paper, Beth Hardtke, the department’s director of communications, wrote in a Sept. 30 email to reporters.

“Our concern is not with your organization, but with those who would impersonate your organization for nefarious means,” Cooper wrote in the Aug. 16 email. “Because of this, we have not made exceptions for any other organizations or entities, and we cannot do so for Wisconsin Books to Prisoners.”

The decision came as a surprise to Wisconsin Books To Prisoners director and co-founder Camy Matthay, who had thought the organization had maintained a good relationship with the department, despite previous attempts by the department to ban its book deliveries.

In May 2008, the department blocked book deliveries from Wisconsin Books To Prisoners after expressing concerns about contraband entering prisons. Help from the American Civil Liberties Union quickly led to that decision being overturned.

In early 2018, Wisconsin Books To Prisoners was told over the phone by numerous prisons that it was barred from delivering books following confusion in mail rooms about whether or not the organization was an approved vendor. However, after Matthay contacted the department's then-assistant security chief, this second ban was quickly lifted, she said.

Wisconsin Books To Prisoners continued to send books for several years with few issues. And before it received the Aug. 16 email citing the department's reason for implementing the new ban, Wisconsin Books To Prisoners “had sent 70,000 books without any instance of contraband. So it was kind of a shock then to get a letter,” Matthay said.

Although the new prohibition still allows for the organization to send new books with receipts, this will greatly decrease the number and variety of books the nonprofit can provide because of its reliance on donated used books and the financial support of donors, according to Matthay.

“I tell people that the reading interests of prisoners is as great and broad as the reading interest of any of the patrons at any public library, so there will be so many prisoners that would be utterly, utterly defeated in terms of their interests,” Matthay said.

These policies affect books being sent directly to prisoners, as well as books entering the prison libraries.

In the Sept. 30 email, Hardtke provided pictures of prison libraries, showing that they are well maintained. However, according to Matthay, who volunteered at a Wisconsin prison for nine years, maintaining a library does not mean that the libraries must always be open and accessible to prisoners, or fully staffed with librarians.

During her time volunteering in a prison, she learned how desperate the men she met were to get “really good reading material,” and how often they felt disappointed by their library’s holdings and limited hours, she said.

As of December 2021, Wisconsin is one of at least 14 states using scanning technology in an attempt to decrease drugs entering prisons through paper mail, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. Prisoners now receive scanned photocopies of their personal mail rather than the original copies.

According to a Department of Corrections incident report provided by Hardtke in an email she sent reporters on Sept. 30, the Oshkosh Correctional Institution found evidence of cocaine in a bundle of books last February that had been falsely labeled with Wisconsin Books To Prisoners as its return address. The books were inspected with other donations using scanning technology and were not given to the intended prisoner because of the positive test.

Although the department requires both vendors and recipients of mail to be notified if the mail is not received, Matthay never received word that any of its shipments hadn’t been delivered or any of the photo evidence, and the organization was allowed to continue shipping more books after February with no issue.

Despite the new policy, Wisconsin Books to Prisoners continues to receive hundreds of letters from prisoners.

“I’m beginning to wonder if there are prisoners writing us to ask us what’s going on, or even to give us information,” Matthay said.

Wisconsin Books To Prisoners is currently meeting and seeking legal options to combat this policy.

According to Braneck, the organization is still accepting donations. Braneck hopes people will continue to spread the word, write to local representatives and sign a letter to the governor and attorney general.