In the early pandemic months, Lucille, Madison’s pizza and craft cocktail hot spot, converted to takeout and delivery only. All of a sudden, workers at the three-story restaurant on Capitol Square had little tipped work, and, as a result, they took home little compensation.

Management got creative and instituted a guaranteed $15 minimum hourly wage by pooling together takeout and delivery tips, and the practice continued when the dining room reopened. Before the pandemic, workers kept their individual nightly tips — but only received a $2.33 hourly wage.

Tipped employees in Wisconsin are some of the Midwest’s lowest paid workers. But some restaurants are restructuring tip-based models of compensation as a stepping stone to instituting greater benefits industry-wide. Part of this restructuring movement was borne out of necessity — tipped restaurant workers needed work in a tipless service environment, and managers needed to pay them. But it also attempts to professionalize a competitive, laborious front-line industry, the inequities of which were exposed amid the pandemic.

“Low-wage service sector jobs come in really difficult packages,” said Laura Dresser, associate director of the Center on Wisconsin Strategy. Bundled in this package is a low base wage with fluctuating tips, inconsistent hours, seasonal cycles of business activity, weak benefits and no sick leave.

Businesses in Wisconsin can choose to pay their servers a subminimum, or “tipped minimum,” wage — an hourly rate below the typical minimum wage. Servers and employers rely on tips to supplement servers’ salaries.

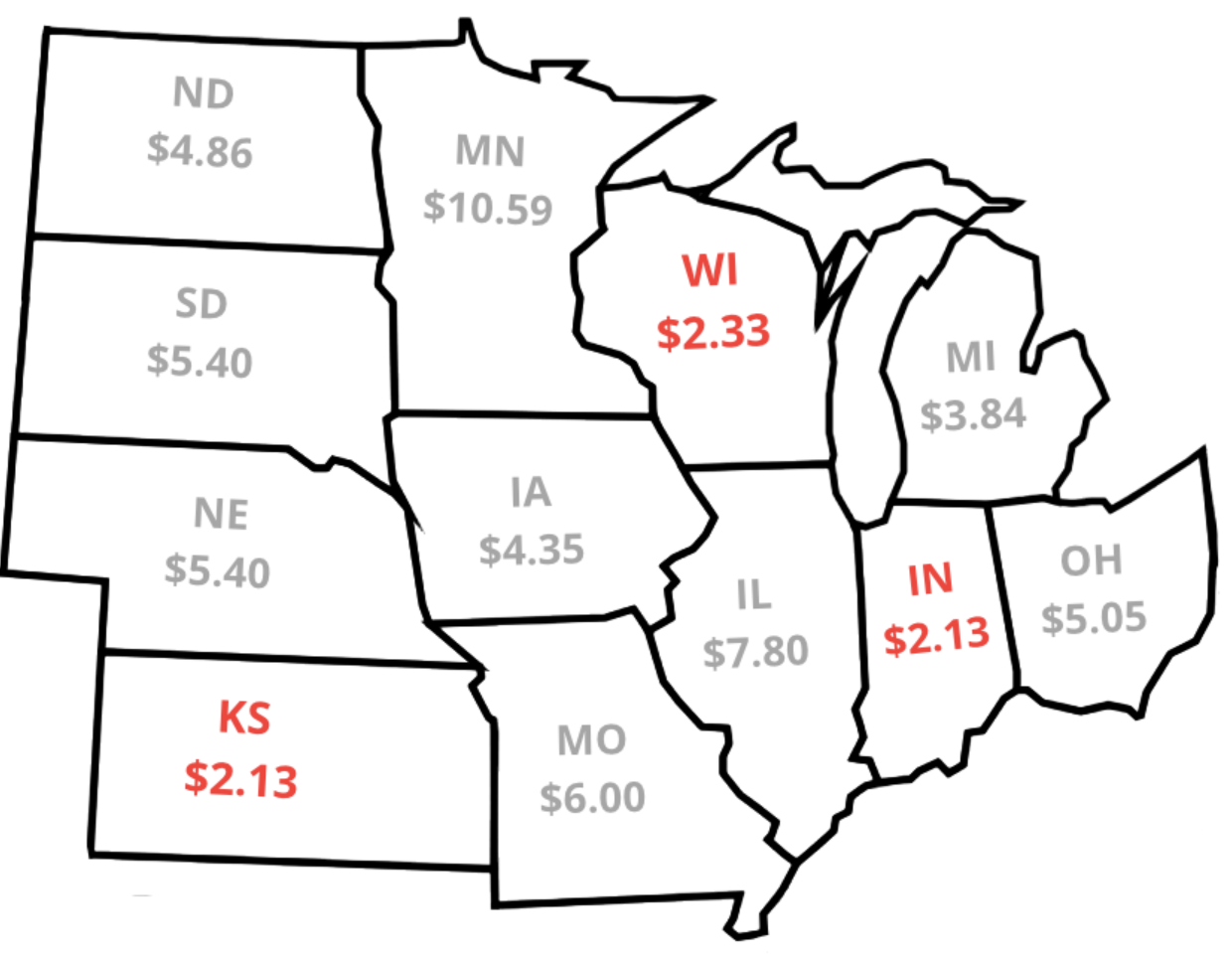

Wisconsin’s tipped minimum wage sits, where it has since 1992, at $2.33 an hour, and it is one of the lowest tipped minimum wages in the region. In comparison, Minnesota, the neighboring state with the highest wage for tipped employees, pays $10.59 — its standard minimum hourly wage — followed by Illinois, at $7.80; Ohio, at $5.05; Iowa, at $4.35; and Michigan, at $3.84. Only Indiana and Kansas, where the base pay for tipped employees is $2.13 per hour, have lower tipped minimum wages than Wisconsin.

The subminimum wage allows service establishments to pay their tipped employees less than the minimum wage, with the expectation that tips will supplement their salaries. Wisconsin’s tipped minimum wage is $2.33, one of the lowest in the Midwest region. Only Indiana and Kansas have lower wages–the subminimum wage in both states is $2.13. Minnesota, by contrast, offers $10.59, its standard minimum wage. While Illinois’ sub-minimum wage sits at $7.80, the city of Chicago eliminated the tipped minimum wage altogether last month. In September, Wisconsin state legislators Rep. Francesca Hong (D-Madison) and Sen. Chris Larson (D-Milwaukee) reintroduced legislation to raise the tipped minimum wage to the state’s standard minimum wage, $7.25. According to Hong, they do not expect the legislation to receive a public hearing. Created by Zoe Jaeger.

“With the subminimum wage, you’re subjecting workers to be at the whims of a customer who may or may not be a fair tipper,” said state Rep. Francesca Hong (D-Madison).

In September, Hong and Sen. Chris Larson (D-Milwaukee) reintroduced legislation to raise Wisconsin’s subminimum wage to $7.25 per hour.

“We know these wages are vastly unjust, and we want every single service industry worker to make a living wage,” Hong said.

Mid-pandemic, Hong — an assemblywoman by day and a chef by night — restructured her restaurant’s staff and raised their base wages.

Hong co-owns and is co-chef of Morris Ramen, nestled on a King Street corner in the district she represents. We met at Morris’s neighbor on the block, Ancora Cafe and Bakery, where fellow community leaders greeted her warmly with waves and hugs.

The pandemic closed Morris’s front-of-house and converted it to a carry-out system — a common theme among Madison’s restaurants. Front-of-house workers, including servers, hosts and bartenders, took on prep or meal-packaging positions with a higher base-pay.

To do this, Morris replaced the subminimum wage model with a tip-share model and provided a guaranteed $15 hourly wage.

Tip-share models gather servers’ tips into a collective pool and disburse those funds to all or most staff members. The subminimum wage model, by contrast, allows an individual server to keep all of the tips made in a given night.

The change stuck around post-pandemic.

“Unfortunately, there are times when we really struggled,” Hong said of the restaurant’s since-increased labor costs. But, she said, higher wages reduce staff turnover, ensure that the restaurant is maintaining a healthy work environment and add longevity and stability to typically part-time service jobs.

The tip-share model allows for consistent wages and increased benefits. But sharing the wealth means sacrificing high-tip payoffs, which servers and bartenders often expect and rely on.

“They of course would rather make more money, and they know that they could make more money somewhere else,” said Joel Wurf, a manager at Lucille, where tip-sharing is now in its third year. “But they’re appreciative of the fact that they have health care, paid time off, a 401(k) benefit.”

To reach their new guaranteed $15 minimum hourly wage at Lucille, servers, Wurf explained, made a base wage of $8 per hour. Then, management supplemented wages to reach the hourly minimum, if servers failed to collectively receive at least that amount through tips.

Kitchen staff and bartenders, too, were guaranteed $15 per hour and benefited from the tip pool.

“Once we realized how much that impacted the team dynamic and how much it worked for us, we just continued it,” said Chloe Christiaansen, director of operations and staff personnel at Rule No. One Hospitality group, which owns Lucille and two other popular Madison restaurants, Merchant and Amara.

Since Lucille implemented tip-sharing in 2020, the restaurant has raised its guaranteed hourly rate from $15 to $16 per hour. Merchant, too, has switched to a tip-share model. And when Rule No. One opened Amara in October 2022, it was with a tip-share model.

“Pre-pandemic, serving was very much a table-shark gig,” Christiaansen said.

A changed compensation model creates new incentives for servers. Christiaansen said the subminimum wage model incentivises workers to fight for good tables and do little else — why would servers help with the dishes when they are being paid $2.33 per hour to scour for tips?

The tip-share model, by contrast, encourages workers to work as a team because their income is not dependent entirely on servers doing a single thing — serving for tips.

“These are the most team-oriented staffs I’ve been around in the industry,” Christiaansen said. “Nobody is able to say, ‘That’s not my job,’ because we’re all contributing to the success of the tip pool.”

Pandemic-era adaptations in the service industry and other low-wage sectors have changed the industries for the better, Dresser said.

The Center on Wisconsin Strategy’s 2023 report, “The State of Working Wisconsin,” showed that Wisconsin’s lowest-wage workers have made the most significant gains over the past three years. Dresser said that equity gains in low-wage work are also helping to remedy the racial wage gap, which remains a persistent problem in Wisconsin.

“To me, this is the most exciting thing about the post-pandemic moment,” she said. “This doesn’t mean the gaps are closed. This doesn’t mean there still aren’t bad jobs. It means that the lowest-wage workers have made the most of the labor market tightness, and it’s been a long time since we’ve seen that.”