The first inklings of fall swept through the Warwick Way Gardens, a community-driven sanctuary for pollinators nestled between tranquil suburban homes in southwest Madison.

Judy Cardin watched as bee enthusiasts sifted through pamphlets outlining simple steps to help pollinators and bumblebee species field guides during the garden’s Oct. 8 open house.

Cardin, a lead volunteer with the Bumble Bee Brigade, a citizen-based organization dedicated to monitoring Wisconsin’s native bumblebees, understands the importance of these moments, particularly in light of the last 20 years.

Whether it’s due to the impacts of climate change, diseases, habitat loss, pesticides or intensified agriculture, Wisconsin’s pollinator populations have experienced a decline. Without these organisms, populations throughout both the state and world could experience a titanic blow. Because pollinators impact over a third of global crop production, their absence would result in a decline in nutriment and access to fresh fruits, vegetables and nuts.

Of the state’s 20 native bumblebee species, roughly half now fall under some type of imperiled status, including the federally-endangered Rusty Patched Bumble Bee.

“Between 20 years ago and now, the Rusty Patched population has declined by almost 90%,” Cardin said. “They used to be a very common bee throughout the United States, but now the populations are only in about nine states. If you look at where their population is the strongest, it’s in Wisconsin. We have a special responsibility because I think we’re their last, best hope for survival.”

Elizabeth Braatz, a conservation biologist at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, is well aware of this trend.

As someone who collaborates with Cardin through the Bumble Bee Brigade, Braatz recognizes the crucial role these organisms play throughout the country, especially in a region dominated by agricultural practices.

“Worldwide, pollinators are important to about 85% of flowering plants, and they contribute to about 35% of global crop production,” Braatz said. “When you think of all the things that we grow in Wisconsin — the pumpkins, cranberries — all those are benefiting from native pollinators. There are multiple factors stressing pollinators out, and when you add them all on top of each other, that’s hard for bees.”

In response to the dwindling number of bumblebees circulating throughout the state, bee aficionados have advocated for community education and involvement efforts, as well as the development of pollinator-friendly habitats, to attempt to rejuvenate these populations.

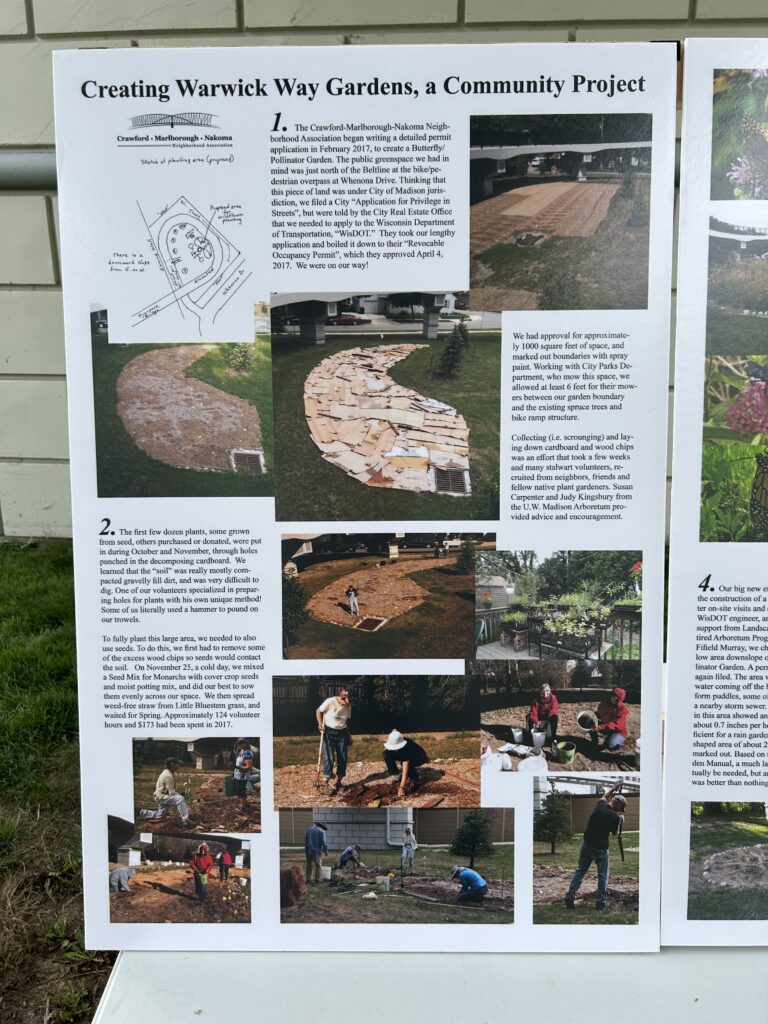

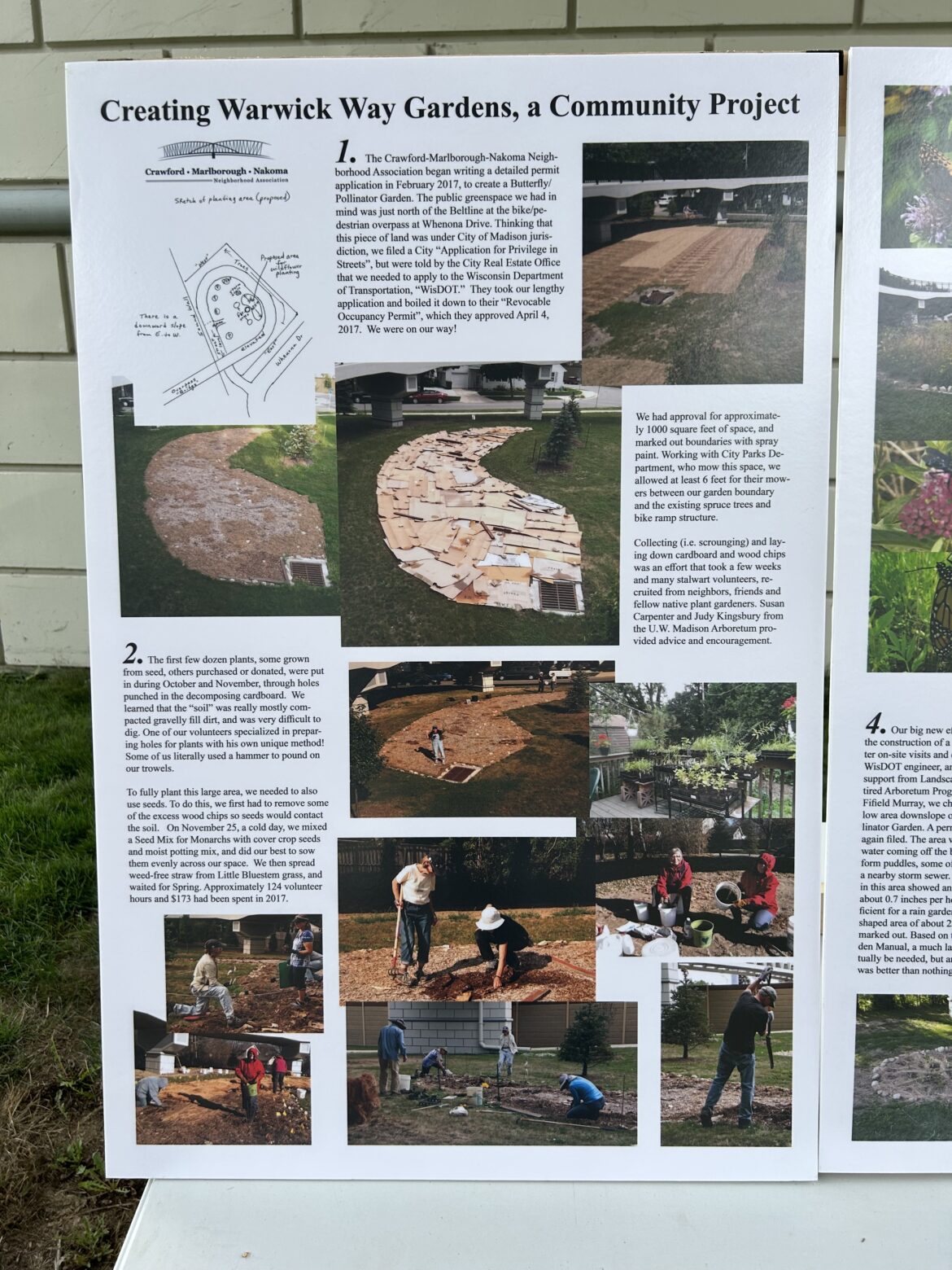

One of these areas, the Warwick Way Gardens, originated in 2017 with the intent to supply monarch butterflies, bumblebees and other pollinators with suitable flowering plants, grasses and shrubs in a public green space.

Powered by the Crawford-Marlborough-Nakoma Neighborhood Association, the garden now exists as an enticing habitat for all species of native pollinators.

Carol Buelow, who helped to establish the garden, has witnessed the natural oasis transforming from a patch of grass to a hub for biodiversity.

“I just looked at the space and said, ‘There's better ways to use this,’” Buelow said. “Our emphasis at the very beginning was focusing on benefitting monarch butterflies, but if you plant native plants to benefit monarchs, you’re benefiting other pollinators.”

Still, success is difficult to quantify. Climate difficulties, like this spring’s drought, impact how folks like Buelow accumulate concrete statistics about pollinators.

Despite the roadblocks, groups like the Bumble Bee Brigade, which partners with public volunteers to monitor and identify Wisconsin’s native bumblebees, attempt to supplement the DNR's own research with data from local gardens and wildlife areas across the state.

“With community science, everyone can participate,” Braatz said. “We’ve had 239 volunteers in Madison up to this fall. In Dane County, we had 12 species verified at 254 surveys alongside 47 participants and six new county records this year thanks to the brigade.”

Ultimately, no single individual or organization can guarantee a steady influx of pollinators down the line. To Buelow, though, these efforts can have a ripple effect in neighborhoods throughout Madison.

“Individuals come and look at this, and they can take ideas back to their own yards,” Buelow said. “That’s the goal—to spread the ideas around.”

The same goes for identifying bees in yards or neighborhoods.

“For every person involved in participatory science, it goes beyond, ‘I took a picture of a bee,’” Cardin said. “It’s that opening of the mind to, ‘I want to know what I could do to make a difference.’ I see every person that participated, every observation that was made, as that symbol of hope.”