When snow falls in Wisconsin, children may think about the snowmen they’re going to build, students may think of the school cancellations they’re going to enjoy and drivers may think about their safety on the road.

When they hear the rumble of snow plows that clear the streets and scatter salt behind them, they likely feel peace of mind that actions are being taken to ensure safe driving.

Wisconsin’s surfaces see more than 650,000 tons of salt dumped on them each year to ensure safety in winter. While spring is technically here, how Madison clears its roads in the winter has year-long effects. Road salts and de-icers melt ice to help prevent harm to drivers and pedestrians, but at a significant cost to the surrounding environment. Road salt finds its way off the road and into the water, soil and air and harms wildlife in Madison’s waters.

In salt’s chemical makeup of sodium and chloride, chloride is what is dangerous. “The chlorides can be toxic to different aquatic life and…are actually lethal to the early life forms” like tadpoles and hatching eggs, said Jim Baumann who is the treasurer of Friends of Lake Wingra, an organization that works to keep the lake healthy and educate residents in the area.

Intensely high concentrations of chloride are found in bodies of water every winter which directly points to road salts as the cause. “There’s no other likely source,” Baumann said.

According to Wisconsin Salt Wise Partnership, a coalition of organizations working to reduce salt pollution in water, it takes one teaspoon of salt to pollute five gallons of water to a toxic level.

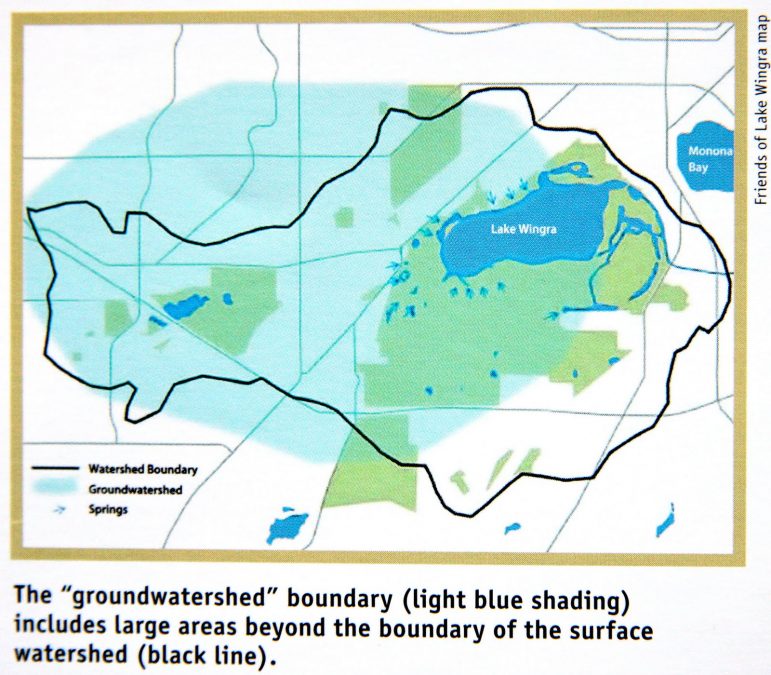

Lake Wingra and its watershed (i.e., the surrounding land around the lake where rain water runs into) is the smallest of Madison’s four lakes and suffers the most from the effects of salts.

Wingra’s chloride concentration level is about 100 milligrams per liter at the surface, the highest of Madison’s lakes. Chlorides tend to sink to the bottom of water, though, so concentration from deeper samples is actually 400 mg/L, classifying Lake Wingra as chronically toxic (chronic toxicity occurs at 395 mg/L according to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources).

Public Health Madison & Dane County reports that chloride levels have been increasing in Wingra by about 2 mg/L each year since 1962.

“It’s very hard for people to see that fish eggs don’t hatch or that tadpoles die [as a result of high chloride concentration]…Where you do see it is you don’t see the reproduction of the fish and you don’t see young frogs and that type of thing,” said Baumann.

Nearly half of the chloride in Wingra comes from salts washed away from parking lots, according to Baumann. Another major source is streets with heavy traffic like Monroe Street and Midvale Road that are identified as “salt routes.” Salts from those surfaces get distributed to the environment by runoff water and by displacement like splashing and spraying from vehicles.

Odana Pond, which is part of the Wingra watershed, has chloride concentrations of 2,000 mg/L just at the surface. Baumann said people who live near the pond have stopped hearing frogs and other amphibians over the years. As a result, Odana Pond is on the state’s impaired waters list, a list of bodies of water that do not meet water quality standards by the DNR.

From the pond, water is pumped out and sent to an infiltration area to become groundwater. Because higher levels of chloride occur in early spring, water is no longer pumped from the pond during that time to avoid pumping chloride into groundwater.

“The chloride levels are [high] enough that…management has been changed to try to reduce the impact of the chloride,” said Phil Gaebler, Water Resources Specialist for the City of Madison.

Compared to other lakes in Madison, Wingra has highest concentrations because it is smaller and has greater percent urban area in the watershed. Monona has about 60 mg/L and Mendota has around 50 mg/L at the surfaces. Levels of both have been increasing by approximately 1 mg/L each year since 1962, half as quickly as Wingra.

Groundwater is affected too, as seen by rising chloride and sodium levels in some of Dane County’s drinking water wells. The City of Madison reports salt has been detected in five of its 22 wells. Though elevated chloride does not affect human health, “saltiness” can be tasted when chloride levels reach around 250 mg/L.

Well 14 on University Avenue contains the highest amount with 45 mg/L and is estimated to reach 250 mg/L in the next 17 years.

Once chloride is in water it is very difficult and expensive to remove.

“It sounds like, oh, just get the salt out of the water, but that is very difficult to do,” said a representative from Madison Water Utility. “This is not a small problem. It will take…likely millions of dollars to fix.”

The City of Madison says the best way to reduce chloride levels is through preventative actions, especially by using less salt on roads.

However, many people overestimate the amount of salt needed to melt ice and keep roads safe, which is a major reason why there is so much salt in the environment. That is why efforts have begun to reduce excess use of salt through training programs that teach applicators what appropriate amounts are.

“People always say, ‘You’re talking about eliminating road salts.’ Well, maybe that’d be nice, but what we’re really pushing is getting rid of the excess applications,” said Baumann.

In 2017, the City launched a Winter Salt Certification Program to teach winter maintenance professionals and applicators how to use de-icing material responsibly and minimally. The City is part of the Wisconsin Salt Wise coalition which targets businesses and homeowners in promoting appropriate practices for reducing salt pollution.

“My goal is that…the reductions are significant enough that we will start to have the trend turn the other way in our lakes, where we are having chloride levels decrease as opposed to increase,” said Gaebler about the program.

In addition to water, salt impacts soil and vegetation. Chloride in soil affects its fertility and density, which makes it difficult to retain groundwater. Affected plants, including trees and crops, have stunted growth and dying limbs. Additionally, salt weakens the concrete, brick and stone that make up infrastructures like homes and roads.

The technology of road salt also has evolved to use less salt. An anti-icer uses a mix of road salt and water to make brine which is sprayed on streets before storms, creating a layer that prevents ice from forming on pavement. The mix is being promoted for state highways and Madison’s salt routes.

Other efforts include de-icers with organic additives which are applied after storms. Cheese brine, beet juice, molasses and beer waste are mixed with liquid salt brine solution to be applied after a storm to melt ice. The additives help salt stick to pavement better so the salt is more effective and less gets washed away into the environment. However, each option comes with drawbacks.

“One of the disadvantages of the beet juice is that…the color of the beet juice looks like blood [on the road],” which frightens some drivers, said Andi Bill, a traffic safety engineering research program manager at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.