In the United States, approximately half a million people use American Sign Language as their primary language at home — a number similar to the country’s population of Italian, Polish or Japanese speakers.

At UW–Madison, between 85 and 100 current students are deaf or hard of hearing.

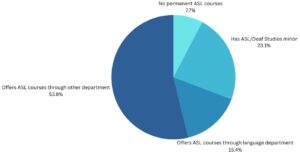

Despite this, UW–Madison did not offer a course in ASL through its language sciences department until 2023. Taught by deaf instructor Taylor Koss, ASL 1 premiered over the summer and was again offered in the fall, with the second level to be an option in the spring.

“Students have asked for it for many, many years,” said ASL interpreter Amy Free. “There’s always a lot of surprise that a Big Ten university did not have it for so long.”

About 15% of adults in the United States have hearing loss in some form, but only a fraction of those use ASL, a disparity often fueled by a lack of access in childhood. Language deprivation is a major hurdle for many deaf children, whose hearing parents may want to prioritize oral communication at the expense of their child’s needs.

“Growing up, there were very few deaf people in my life. I thought that I was one of the only deaf people in the world. When I went into the [Wisconsin School for the Deaf], that really opened my eyes to the community,” Koss, whose parents are hearing, said through an interpreter. “I decided that my passion was actually to learn ASL and teach ASL to other generations of people, so that they have equal access to education.”

During the 2023 fall semester, the ASL 1 class met four days a week and was taught immersively in ASL through a mixture of lecture and discussion.

The curriculum Koss uses, True Way ASL, was created by a group of deaf ASL teachers and highlights the diversity and variety of intersecting identities within the Deaf community.

“[Koss] not only teaches ASL, he explains and puts in history lessons [on] Deaf and hard of hearing culture,” said sophomore Heaven Williams, one of the ASL 1 students. For instance, she learned that “people who are blind can have a guiding person with them when they sign, and when they sign they’re kind of holding your hand, so they can feel the sign.”

ASL 1 is not the first sign language class ever offered at UW–Madison. One has been offered through the department of Communication Sciences & Disorders for more than 30 years, but it looks very different from the one piloted this year. That course was geared toward future medical and education professionals who will work with children, while the language department’s new course focuses on interpersonal communication between adults.

“The vocabulary in my class might include things like ‘ball’ and ‘giraffe’ and ‘bottle’ and ‘diaper,’ whereas the class that’s taught in the [language sciences] department likely would have, maybe, travel words, for how you are going to go on spring break,” said emeritus clinical professor Michelle Quinn.

Quinn taught the department’s sign language class until her retirement in 2020.

Note that it is described as simply “sign language,” not ASL. ASL is only one of many signed languages around the world, and it meets the five components of language as defined by linguists.

“People still misattribute that ASL isn’t legitimately a language. They think of it as just a tool, or a bunch of gestures,” Free said. “And it’s none of those things. It’s its own language with its own grammar, its own syntax.”

There are many signing-based forms of communication besides independent languages. These methods include home-sign gesturing, which Koss used growing up with his family, and Manually Coded English, which Quinn initially taught when her course debuted more than three decades ago.

These systems often involve using signs and speaking English in tandem, whereas ASL is linguistically separate from English and does not map onto it.

“There’s a continuum from signing every single syllable of an English word — that’s not really used anymore — all the way to ASL, where you don’t use your voice at all but you use your facial expressions and your body language and your hands,” Quinn said. “ASL is not a word-order language, it’s a topic-comment language. Three people who are fluent in ASL might sign very differently a sentence that says ‘What did you think of the movie?’”

The move to pioneer an ASL course at UW–Madison was more than 25 years in the making. In 1993, the Faculty Senate voted to recognize ASL as a language worthy of being taught for credit.

The communication sciences & disorders department, along with the McBurney Disability Resource Center, told university administration in the late 1990s that UW–Madison should have a Deaf studies program, but they were not moved by the idea as UW–Milwaukee already had such a program.

Later, Quinn’s department attempted to add a Deaf studies “wing” and changed its name as part of this effort after consulting with deaf people. Previously, the department was called simply Communication Disorders.

“ASL is not a communication disorder. It is indeed its own language,” Koss said.

With that in mind, housing the new courses under the language sciences umbrella was a prime goal, instead of marketing them under the spectrum of disability and special education. Many Deaf people identify themselves primarily as members of a linguistic and cultural minority, rather than as disabled.

“That is the identity that they want out there and established — not framed in the impairment, the ‘can’t,’ the inability, the disability… but the ‘can,’” Free said.

ASL 1’s class roster consists mostly of hearing students, with one deaf student who uses a hearing device. Interest in ASL among hearing people has grown in recent years, thanks to signers on TikTok and Best Picture-winning film CODA, and Koss sees his class as one way to correct misconceptions and expose students to Deaf culture from a firsthand source.

He hopes the program will grow in years to come.

“I am very supportive of those students going to Deaf events and meeting the Deaf community in Madison. If a student shows up at a Deaf event, I’m always so happy to see them,” Koss said. “I hope that we can expand our deaf staff and that way, we can start growing a very successful ASL program at UW-Madison.”