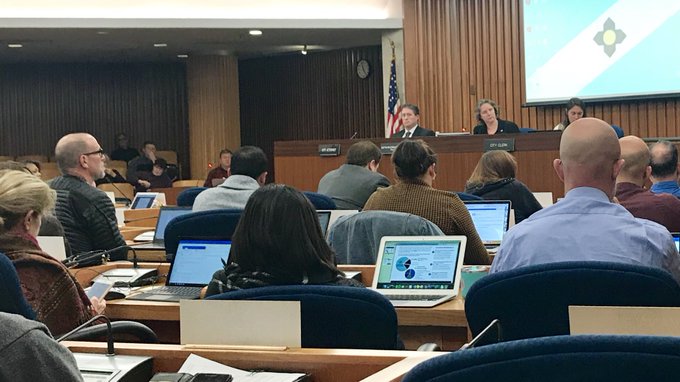

The Madison Common Council is debating whether to add a referendum to the spring ballot that would ask whether the council should undergo structural changes by making alder positions “full-time,” increasing their salary, decreasing the number of alders and implementing term limits.

The proposed resolution is based on the recommendations of the Task Force on Government Structure, created in September of 2017. The Task Force was instructed to examine the city of Madison’s existing government structure, and evaluate whether residents were receiving adequate and fair representation.

Ultimately, the Task Force concluded “the City’s current government structure is an impediment to full participation and representation and, therefore, that the City ’s structure isbfundamentally unfair to a large portion of the City’s population, including, most notably, the City’s residents of color and low income.”

Historically, Madison alders are considered part-time employees, as their annual salary comes to approximately $13,700. Most alders have full-time jobs, and must volunteer their extra time to the position. This is why the task force recommends that the pay for alders be increased to about $67,000 per year and that the number of alders from 20 to 10. Furthermore, the Task Force recommends increasing alders’ terms from two to four years.

Sue Pastor, a founder of the Greater Sandburg Neighborhood Association and former co-chair of Progressive Dane, says that reducing the number of alders by half, and therefore increasing the size of each aldermanic district, is her main objection to the recommendation.

“I feel like, as it is, it is difficult enough for constituents to hold accountable to the district the people that they elect, and with the increase in (district) size, I fear that that becomes even more difficult,” Pastor said.

Alder Samba Baldeh of District 17 voiced his concerns about resizing the council in the Wisconsin State Journal, saying that it would require increased campaigning, forcing candidates to invest money into campaign managers and media buying.

Carrie Rothburd, a spokesperson for the Bay Creek Neighborhood Council, echoed this.

“I'm not sure that if we professionalize the jobs--which requires more campaign funding--I'm not sure that we have taken care of the problem and that we will, in the end, have a more representative Council,” Rothburd said. “I think we need to explore this more rather than jump to the conclusion.”

Alternatively, John Perkins, Neighborhood Contact Person for the Greenbush Neighborhood Association, said that an increase in salary would likely allow more opportunity for those who are interested in becoming an alder but cannot do so right now.

“There are a lot of people that work full-time; they may be working two jobs, they may be working three jobs in some cases,” Perkins said. “And for someone in that situation to take on a supposedly half-time job as alder is just not feasible, because people may be struggling just to get the bills paid and the rent paid and food on the table and whatever else it may be.”

In the city of Chicago, alders are considered “part time,” however, they make anywhere from $106,000 and $117,000, which differs greatly from Madison alders’ average salary of $13,700.

Perkins also recognized that reducing the number of alders could leave them in a tough position, as not all those who live within one district may share the same opinion about an issue, and it can lead to inequality between different groups.

“People in the less affluent areas are the ones that this whole proposal is kind of targeting, and if they get someone who’s not as experienced in how city government works, they may kind of get shafted in the decisions that are made,” Perkins said.

Rothburd pointed out that many neighborhoods already face disadvantages in Madison.

“There are some neighborhoods that, historically, have been overlooked in alders’ districts,” Rothburd said. “And that may be because the particular neighborhood is not as well-organized, doesn’t have neighborhood associations, or because of the way in which the neighborhood association has chosen to structure itself.”

The result, Rothburd says, is that these neighborhoods often receive less attention from their alders, and their concerns are not taken seriously.

“There's an erroneous belief at the heart of this, which is that the city interacts democratically with its residents and would do so evenly, if not for disparities around race, around poverty and around the intersection of race and poverty,” Pastor said. “The truth is that the city listens to very limited white perspectives.”

In a follow-up email, Pastor added, “And the city is much more likely to listen if they like what they are hearing.”

Therefore, Pastor said it’s incorrect “to believe that we will correct disparities by electing one person out of a particular demographic” and that it would be sufficient for representation.

Pastor also said that alders often get bogged down in “average, mundane constituent issues,” like potholes, and therefore are unable to collectively address policy issues.

Madison previously explored the idea of setting up a 3-1-1 system to report resident concerns, however, the proposal languished, Pastor said. In comparison, Chicago does have 3-1-1 services, which offer a direct phone number, a website and a mobile app for residents to report a number of issues, including those related to transportation, garbage and recycling, and public safety.

Pastor said that lack of a 3-1-1 system or an office for residents to voice these types of concerns forces Madison residents to bring up issues at city council meetings, which can be an unpleasant experience.

“It's bureaucratic and alienating to have to go and talk to Council for your three minutes,” Pastor said. “Someone will bark at you and tell you to stop when it's over.”

Ultimately, Pastor said, the city needs an overhaul of their fundamental practices before they try to follow through with restructuring, and Rothburd agreed.

“This is sort of like the icing on a cake that hasn't been baked,” Rothburd said.