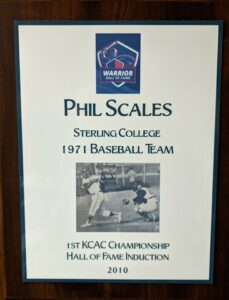

The bases are loaded and Phil Scales just walked up to bat for the Sterling College baseball team.

“If we win this first game, then we will win a KCAC championship, which they had never won before,” Scales said. “I came up to the plate with the bases loaded, two outs in the last inning, and I hit a double and knocked in two runs. We won the championship!”

Not only was Scales the only starting freshman on the team that year, 1971, he was also the only Black ballplayer. He had made history, in more ways than one, and yet his day was still far from over.

“All my teammates ran out and put me on their shoulders,” Scales said. “I’m kicking and screaming, saying, ‘Recital! Recital! I have to do this recital!’ They put me down, and I ran across the field to the music room. I go sit down at the piano, and for 10 seconds I cannot remember what I’m supposed to play — I’m just so geared that we just won a championship.”

Over the course of his career, Scales has played in or conducted for more than 10 symphony orchestras and created a name for himself in the music industry. He has transformed orchestras by increasing the number of players nearly tenfold, and he has even started some of his own orchestra groups. Although Scales grew up in Pittsburgh, he made a home for himself and his family in the Midwest, taking his talents with him from Kansas to South Dakota and, finally, to Madison.

Where it all began

At 5 years old, Scales fell in love with music while watching cartoons.

“I remember seeing Bugs Bunny chase Elmer Fudd around the barbershop trying to cut that one little curl and in the background was [classical music],” Scales said.

However, that was not the only show that left an impression on young Scales, because every Sunday at 2 p.m., “The Lawrence Welk Show” came on.

“Lawrence Welk was a white conductor, and he had a baton that had to be 2 and a half feet long and a white tuxedo. He started out, ‘And a one and a two and a three and a four,’ and his orchestra would play,” Scales said. “I loved that show and would just be in awe of it… that’s what hooked me into wanting to be a conductor.”

Scales’ musical life officially began in the fourth grade when he started playing the violin. This was not without its challenges, but through his love for music, Scales persevered.

“Back in the late ’50s in the inner city of Pittsburgh, it wasn’t really cool for a young Black kid to play the violin. So I remember coming out of school and kids throwing rocks at me and things like that, but I fell in love with the violin,” Scales said.

By the time he was in seventh grade, he was so far ahead of his class that he started to play the viola as well.

By ninth grade he was the concert master for his high school orchestra. At this point he also decided to audition for the Pittsburgh All-City Orchestra, an orchestra that picks the best string and wind players in the city to rehearse and perform concerts — and he got it!

“I was playing violin in my high school orchestra, and I was playing viola in the All-City Orchestra,” Scales said.

It was from here on that Scales’ plans really started to come together. He realized that if he did well enough in football and baseball, there was a good chance he would get a scholarship for college.

“My sports ability I wanted to get me into college, and then my music ability would get me into society,” he said.

Life at Sterling College

Scales was able to make his plans come true, and in 1970 he started his freshman year at Sterling College in Kansas as a music major on a football and baseball scholarship.

But that is not the whole story. To be a conductor, a student must learn to play every instrument. This typically takes five years to complete. His scholarships only covered the costs for four years.

So, on top of playing football and baseball, Scales took 18 to 21 credits each semester to graduate in four years.

“I was a music major, and I was an athlete,” he said, “and music and sports in college was like oil and water.”

Every day at 3:45 p.m. Scales had to be on the field for football practice. Every Tuesday he had piano lessons until 4:15 p.m.. Every Tuesday he had to run extra sprints.

Yet running extra sprints was the least of his problems, because one of the requirements to be a music major was participating in marching band. To get an A in marching band, students had to perform at the football game halftime show.

“Well, I was on the football team and I said, ‘Prof, we have a problem. There’s no way I can run out there and change my uniform and march in the band, and I’m certainly not marching in my football uniform.’ And [my professor] said, ‘Well, Phil, I’ve never had this problem before,’” Scales explained.

Unfortunately, he was never able to find a solution for this dilemma and ended the class with a B minus.

Life after college

After college Scales knew he wanted to become a professional conductor.

So he sat down and asked himself, “What do I have to do to become a professional conductor? Why should someone hire Phil Scales?”

He decided that to make this happen, there were three things he needed to do: learn how to be a master teacher, recruiter and motivator.

It would appear that Scales found success in his endeavors, as he took the first orchestra he ever worked for, one at a junior high in Hutchinson, Kansas, from 15 kids to 140 over four years.

He then moved to the high school where he also worked as the football coach. It was here that he met his wife, Martha, who he has been married to now for 41 years.

She was originally from South Dakota, and her friend alerted her to a soon-to-be job opening in the Watertown school district.

The current orchestra director was about to retire, and Scales was ready with a plan:“I moved my family to Watertown, South Dakota, in March of ’86, so I could be in the community, established for when he retires, then I can apply for his position”

When the time came for a new person to step in, Scales was more than ready.

During the interview they asked him what his five-year plan was. Once again, he was able to show off his ability to transform an orchestra.

“In five years we will have over 100 kids in junior high orchestra. These kids will play well enough that we will play at the state music convention, and we may have the opportunity to apply for nationals, which are held in Chicago,” he said.

Within three years, Scales had a group of 135 kids. By year four, they played at the state music convention, and by year five they sent in a tape to the Chicago nationals and were accepted.

Unfortunately, the superintendent did not want the middle or junior high to go on trips outside the state, and they were unable to go to Chicago.

In 1988, the head of the Heron Symphony called Scales and asked him to be a guest artist. He ended up conducting there for 11 years.

In 1992, Scales started two symphonies in Watertown: the youth symphony, which he started in July, and the Watertown symphony, which he started in September.

For eight years he worked in all three symphony orchestras. The Heron Symphony on Monday nights, the Watertown symphony on Tuesday nights, and the youth symphony on Saturday nights.

The journey to Madison

As time went on, Scales wanted his family to live in a place with more diversity.

One morning, Scales was getting ready for school and told his wife that when he came home for lunch, she should have a place in mind for them to move to.

“She said, ‘What do you mean, move anywhere?’ I said, ‘Pick a place for us to move.’ Again, she asked where,” he recounts. “I said, ‘Baby, I’ll follow you anywhere.’”

When he came home for lunch, she had information about Madison on the table.

They came to Madison for a week to see where they may want to live, but at the time, Madison was no more diverse than South Dakota. Still, the Scaleses wanted to move here, so they came back to visit again with their two oldest sons, who were in high school, and let them pick which school they wanted to attend. The family officially moved to Madison in 2000.

Then, after decades of work, Scales conducted his last show with the Hartford Youth Symphony in 2015. This was a group of 11 kids and beginning fifth graders.

So what now?

After retiring in 2015, Scales picked up a job as an Uber driver. He has now been doing this for over six years, has over 26,000 trips and, most importantly, still has a five-star rating.

“I am an ambassador for Madison,” Scales said. “I love it when they do big things out at Epic because then they have people come into those meetings from all over the world, and they fly into Madison, and they get into Phil Scales’ car.”

With so many trips under his belt, it is safe to say that many people have been able to learn more about Madison thanks to Scales.

There are hundreds of Uber drivers in Madison and Dane County, but there is only one Phil Scales.

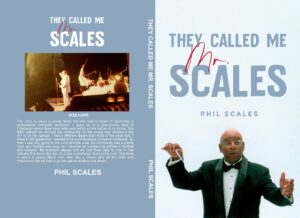

It is evident that Scales has lived an enticing and fulfilling life that seems almost too good to be true. His book, “They Called me Mr. Scales,” gives a more in-depth look into his life.

For anyone that may be interested in his book or his story, he will have a book signing on Saturday, March 16, from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. at the West Towne Mall Barnes & Noble.