The Madison Public Library has changed since its inception but mission remains the same

In 1875, Madison was a small town on the rise. The capital city of Wisconsin was a town with a population between 9,000 and 10,000 people. Immigrants were coming to America, and the Civil War had only ended a decade before.

That same year on May 31, Silas Pinney, Madison’s 13th mayor, would create the city’s first public library after the Wisconsin state legislature passed a bill in 1872 allowing municipalities to collect taxes to support a library. What was called the Madison Free library opened in two rooms inside City Hall at 206 N. Carroll St.

Since its inception more than 150 years ago, the library’s mission remains the same: providing the community with free access to information. It’s one of the last bastions where there is no expectation to spend money.

At the time, citizens were encouraged to donate their own books, which according to the Madison Public Library records, added 200 books to the collection, continuing its tradition of strong community support.

Today the library has eight locations within the city, and works with more than two dozen outside of city limits.\

Before the city created Madison Free Library, it was a subscription-based book borrowing service, said Tana Elias, digital service and marketing director for the Madison Public Library. People could borrow books by ordering titles through the city.

"Mr. President, Ladies, and Gentlemen, the founding and opening of a free library, which is to diffuse its advantages and confer its blessings on all alike, whether rich or poor, of whatever condition, is an enterprise and an event of marked public interest and importance,” Pinney told the crowd when the library first opened.

Virginia Robbins was hired as the first librarian with a salary of $400 a year, equivalent to just under $10,500 today. She kept a big ledger where she tracked what books people checked out and when.

She also used beans to keep track of the books checked out, which seems like a rudimentary method, but worked for the first library. People could place a bean in a collection box for different genres like history, literature, religion, travel, fiction and science, so Robbins could keep track in addition to her ledger.

“One of the first branches that opened it had a reading room for immigrants,” Elias said. “It was a place where immigrants could study or learn about news from their homeland.”

The first library that opened remained open on Saturdays, which meant that immigrant workers could use their days off to go to the library. This was new at the time, since most businesses closed for the weekend, Elias said.

More than 100 years later, the library continues its mission of literacy work, Elias said. By offering English Language Services, immigrants continue to use the library in navigating a new country, she said.

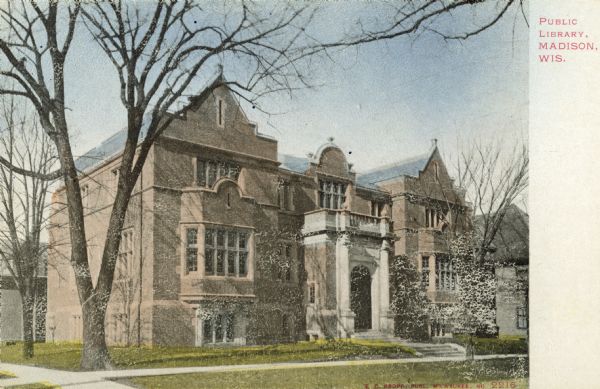

The first library separate from City Hall opened more than 30 years later as a Carnegie Library in 1906, which still operates in downtown Madison as the central library.

“One thing that strikes me in leafing through the history of Madison Public Library is that even at the beginning, the library sought to expand access by opening up additional locations — in stores, in schools, and eventually in new dedicated spaces,” Elias said.

The library still spreads material outside its brick and mortar locations through programs like the Dream Bus mobile library and community events the library hosts, Elias said.

While the library has undergone a number of changes since its inception, it still aims to provide information and a meeting place for the community regardless of if they can pay or not, especially in the face of rising wealth inequality.

The library aims to be a welcoming place for LGBTQ community members, immigrants and other marginalized groups in the community, Elias said.

“We’re really intentional in thinking about equity,” Elias said.

The services that libraries offer are different than at their inception, but the tenets remain the same, Elias said.

The library has always been about helping people navigate information, Elias said. Patrons can find resources on a range of subjects including how to file their taxes and the process of going through a divorce, she said.

“Libraries are one place where people can get relatively unbiased media,” Ellis said.

This collection of stories by professional master’s students in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication explores a series of first experiences, contributions and movements across Dane County.