Most City of Madison officials have billed the city's upcoming Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system as an important method to increase city-wide sustainability. However, variables such as ridership, implementation, and cohesiveness with other city systems have the potential to create negative environmental externalities if the project is not executed properly.

“As long as this project is done responsibly and in line with current environmental protections, I think we can be confident [that Bus Rapid Transit] will be an added benefit to the Madison area,” said Jonathan Drewsen, communications director for Clean Wisconsin, the state’s oldest and largest environmental advocacy organization.

Clean Wisconsin is one of many parties involved in Madison’s BRT initiative. These parties deal with more than just the environment; with a projected cost between $120 and $130 million, Bus Rapid Transit is a massive undertaking that requires planning studies on ridership, construction, and vehicle maintenance, among other things. Many of those considerations have been thoroughly studied to this point. Environmental impacts have not.

“We [have] not run any detailed environment impacts on this. We are just not at that stage yet,” said David Trowbridge, planning manager of Bus Rapid Transit. Trowbridge said that the federal environmental review process will be completed by the end of 2021, two years before implementation is scheduled to begin.

As of now, there is only one major issue concerning BRT and potential negative environmental effects; the renovation of University Avenue.

“I am not aware of any concerns at this time beyond a standard road reconstruction project,” said Eric Heggelund, an environmental analyst and transportation liaison for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

The reconstruction is standard in the sense that it is needed regardless of Bus Rapid Transit, as University Avenue is not well equipped to handle the ever-increasing traffic of Madison and Dane County. However, there are elements of the construction that would be unnecessary without the implementation of Bus Rapid Transit.

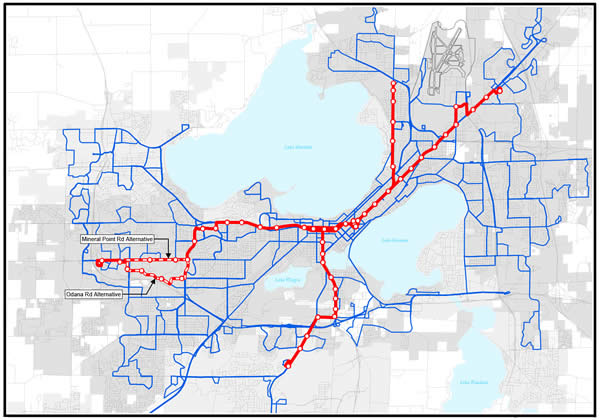

In order for BRT busses to operate effectively, at least fifty percent of the route must consist of BRT-only lanes, said Ben Lyman, a transportation planner for the Madison Area Transportation Planning Board. Madison has never had a BRT system, so these lanes don’t yet exist.

Compounding this problem is the fact that University Avenue cannot be widened due to residential, commercial, and environmental circumstances. In order to create these special lanes, the road will need to be reorganized.

Jonathan Mertzig is a board member of the Madison Area Bus advocates, and a self-described “transit geek.” He has analyzed and used various BRT systems around the world. Mertzig finds that environmental impacts are smallest when BRT routes are “largely within the footprint of existing roadways."

This decreases the need for preliminary renovation, and with it, the debris and exhaust created by construction. But the required remodeling of University Avenue adds another layer to an already-complicated issue.

The $24 million renovation will commence prior to the completion of state and federal environmental reviews. This could cause strife in the timeline if the positive environmental effects of Bus Rapid Transit are found to be less substantial than current projections estimate.

Heggelund believes that to be an unlikely scenario. “The city of Madison reconstructs roadways every year. [Reconstruction projects are] required to follow applicable regulations to reduce impacts,” he said. Heggelund named “erosion control, endangered species requirements, and wetland and waterway regulations,” as examples of those impacts taken into account by officials.

Madison’s unique layout has led local officials to become especially familiar with time-sensitive road reconstruction projects that require diligent environmental analysis. As one of only two major U.S. cities built on an isthmus, there is little room for transportation planners to work when it comes to redesigns for roadways or shifts in traffic flow.

Mertzig acknowledged that the isthmus does not afford Madison a “gold standard” of BRT layout. However, he also noted that Seattle, the United States’ largest isthmus-bound city, has become a shining example of Bus Rapid Transit management.

“Only a handful of North American cities have grown transit usage enough in the last decade to have a drop in pollution that can be correlated with mass transit expansion. The only city I can think of that really has impressive results is Seattle,” he said.

The initial implementation of Bus Rapid Transit is not a “mass expansion,” as Mertzig put it, as much as it is a reworking. That does not mean the positive effects of Bus Rapid Transit will be insignificant. According to a memo on BRT published by the city in October 2019, “the environmental benefits would likely be medium-high or high,” on the Federal Transit Authority’s Environmental Benefit Measure. Medium-high and high are the two highest categories on the five-part scale.

The most significant fence post standing between the city of Madison and a worthwhile, sustainable Bus Rapid Transit system is ridership. Simply put, officials have to convince people to put down car keys and pick up bus passes. If BRT riders are the same group that already utilizes city buses, positive environmental impacts will be faint.

Preaching sustainability is not enough, according to Drewsen. “Most people think more in terms of convenience than in terms of sustainability,” he said. “If BRT ends up being a better option than driving from a convenience standpoint, there’s a good chance it will be widely embraced.”

It is yet to be seen how enticing of an option Bus Rapid Transit will be for Dane County Commuters. A variety of people involved in the project expressed excitement about future BRT use, but that means little if their less-transit centric peers stay away.

Mertzig highlighted two hypothetical paths for the project. “If we throw millions of dollars at a line that only benefits a small slice of Madison and only offers a minuscule improvement over existing options, we won't succeed in drawing people to transit,” said Mertzig, adding, “If we do things right, [if we] don't cut corners on BRT design, and use BRT as part of a holistic approach to improving transit, I think it should be worth the investment.”

An efficient, attractive Bus Rapid Transit system will entice riders, and, in turn, help make Madison more green. An impotent, limited system will keep private cars on the road, gasoline fumes in the air, and ultimately cause more harm than good. The city has lots left to do if it is to turn this expensive, revolutionary transit method into a sustainable, popular reality.