For the people of Madison and its suburban transit partners (Fitchburg, Middleton, Town of Madison, and now Sun Prairie) it might seem obvious that the primary purpose of a locally-owned and operated public bus system is to address the transit needs of the people in the service area. They pay extra property tax to support it, whether indirectly through their rent or lease, or directly on an owned home or business.

Presumably, that would mean that before allocating TIF (tax increment financing) or other money to facilitate the travel and parking of suburbanites from neighboring communities into downtown or other parts of Madison, city funds would first be oriented toward the transit needs of people who live 24 hours a day every day of the week in the service area itself. Buses would run frequently. Routes and stops would stay constant with rare exception. Many more bus stops would have shelters, benches, signage, concrete pads and lighting.

Before investing in an infrastructure that facilitated suburbanite travel downtown, city funds would go toward a bus service designed to enable residents to live a good life in the area without having to own a car. The cost of owning and maintaining a car was recently estimated to be $737 per month or upward of $8,849 annually. That is more than the total average property tax on an owned home in Madison. And having to rent a parking stall along with an apartment can add substantially to the rent.

Wiser investment in Madison’s own infrastructure would enable residents to comfortably take the bus to a parent-teacher conference or a medical appointment. People could take the bus to second or third shift jobs or to overtime work scheduled for a Saturday or Sunday. Residents could attend a Common Council or similar meeting to its end because buses would still be running when the meeting finished. Bus users could shop for groceries without being denied entry into a bus because they had too many packages or take so long to get home that all their milk had gone sour and all their frozen food had thawed. They could partake of evening entertainment, whether at the Overture Center, a hip hop venue or elsewhere.

Presumably, an enlightened bus system would be dependable enough that bus users could sign a 12-month lease or purchase a home based on where the bus ran at the time. Children, parents or employees of residents who do not ride the bus themselves could use the bus to, among other things, travel to that person's residence. Taxpayers would be investing in themselves first and only secondarily in people who lived in communities outside the service area. If commuters to the service area liked what they saw and wanted that service too, they could have their own communities partner with Metro or move into the service area themselves without being considered a “sucker” for paying taxes to support Metro.

Yes, this is a dream because buses do not run late enough, early enough, frequently enough or constantly enough. Some only run for a few hours in the morning and few hours in the late afternoon of weekdays. Too many bus stops are not adequately endowed with shelters, benches, lighting or trash cans, or adequately cleared of snow in the winter. Even medical facilities are often located without attention to access by anything but a car. Bus stops get moved away from work places by a clueless engineer fixated above all else on the distance between bus stops. So as a public agency, is Madison Metro Transit's mission to deal with such issues and maximize transit service for residents in the Metro service area? No.

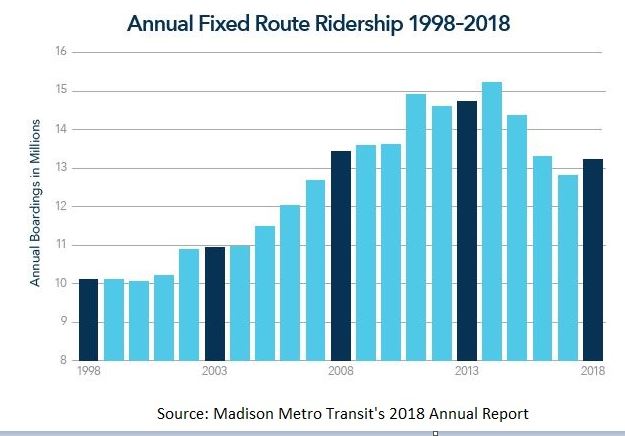

Metro’s stated mission is: through the efforts of dedicated, well-trained employees, to provide safe, reliable, convenient, and efficient public transportation to the citizens and visitors of the Metro service area (bold added). And it measures its performance by touting ridership numbers. For instance, Metro's latest (2018) annual report tells us: "In 2018, Metro experienced ridership gains for the first time in several years." This pronouncement is accompanied by a graph showing Metro's annual ridership numbers since 1998, a graph the GM trots out every chance he gets (see accompanying graph). In explaining her special focus on rapid buses in her recently-released capital budget’s executive summary, Madison's mayor unabashedly wants to expand bus service "with the goal of seeing annual ridership reach 18,000,000."

Great. But maximizing the transit-related welfare of would-be bus riders and other residents in the local taxing area is not the same as maximizing ridership numbers. In fact, the two goals often conflict in what is sometimes referred to as the “ridership/coverage tradeoff.” This may seem surprising to many, and in the case of many places including Madison, may have roots in the fact that the bus system used to be run by a private company. That officially changed April 1, 1970 however, after years of wrangling, a two-month bus strike and much political drama.

Maximizing ridership is the main goal of a business whose income depends on fares. It is only one goal of a public agency however – especially a public agency that only receives a quarter of its revenue from fares. Rather, a public agency must try simultaneously to maximize such features as equity, civic engagement, well-being, shared prosperity and good stewardship. Yes, there must be tradeoffs when trying to meet all those goals, but an inadvertent side effect of trying could actually boost ridership numbers as well.

In the end, we need good city planning and we need to follow those plans. Good city planning ties land use to transportation. It minimizes necessary tradeoffs between our core values while maximizing our ability to walk where we need to go. It facilitates the safe use of bicycles or transit for going longer distances. For instance, truly affordable housing would be located in walking distance of employment, neighborhood centers, schools and food markets. Affordable housing would also be near a good bicycle way and a main transit line. It would be next to a safe and attractive bus stop as well as a crosswalk leading to another stop with similar qualities directly across the street. In a well-planned city where the well-being of transit users is maximized, most tenants and homeowners would not have to own a car but could if they wanted.