Over the course of an hour on a warm Monday afternoon in May, no fewer than 30 people passed through a small, tree-filled city block on Madison’s east side. Orton Park, Madison’s first city park, sprawls across 3.5 acres of the Marquette Neighborhood, just one block off of Lake Monona.

As a persistent wind roiled the still-cold water of the lake and swayed the barren branches of tall oak trees that are now well over 175 years old, it also seemed to blow passers-by through Orton Park. Some runners and dog-walkers spent only minutes in the park as they cut through a diagonal path that bisects the less than 4 acres of city land. Some stuck around for a while longer. A father sat on a bench and watched his two daughters run around a metal play structure. A mother and her sons drew with chalk on the floor of the park’s centerpiece, a white-pillared gazebo on a raised stone platform.

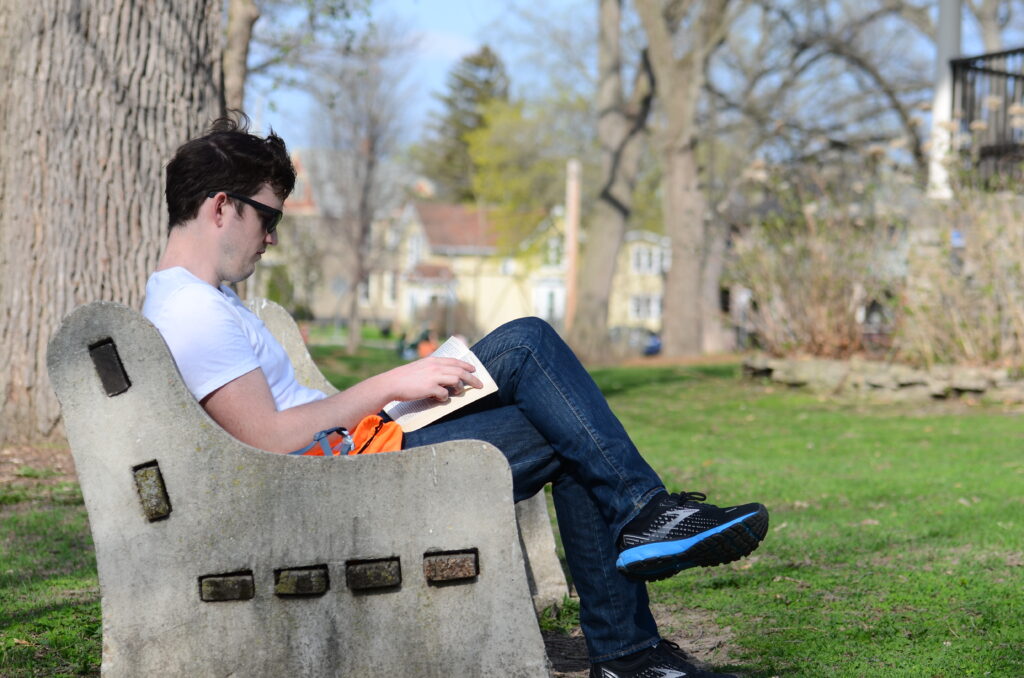

Adam King, a Madison resident originally from Kentucky, stopped to read a book on a bench along the path. He said his bike wheel broke during a ride through Madison, so he dropped it off for repairs and decided to walk home, visiting Orton Park for the first time along the way. “It’s a nice park,” he said, “It’s calm.”

People have been visiting Orton Park for 135 years, since the site was established as Madison’s first municipal park. Save for a couple commemorative plaques, the unassuming park gives little indication of its rich and unique history.

After Madison was established as a village in 1846, the Trustees purchased a lot intended to be a cemetery in the Sixth Ward. The land upon which Orton Park now sits was divided into 256 burial plots. However, after just six years, the Trustees realized that a 3.5 acre lot was inadequate spacing for their healthily growing village. After Madison’s city charter went into effect in 1856, the Common Council selected a new site, the Forest Hill Cemetery.

In 1875, John George Ott, a Swiss immigrant who served as an alderman and county supervisor, petitioned the Common Council of Madison to remove the cemetery and establish a park in its place. He and a few other Sixth Ward residents made the effort to raise money and improved the park themselves. The council approved, and all the remains that could be found were removed and relocated to Forest Hill Cemetery. The park was named for Harlow S. Orton, then a state Supreme Court justice and former Madison mayor. In 1887, Orton Park officially opened, the first park in Madison’s city limits.

The park has always served as a front yard for neighborhood social life. In the 1880s and 1890s, residents planned and hosted frequent band concerts and the Ladies Aid of Pilgrim Church (now the Wil-Mar Center) held regular ice cream socials. To this day, the park is bustling with neighborhood activity, including one of the focal points of summer in Madison: the Orton Park Festival, an annual event that dates back to 1965. Originally, the park’s neighbors would have regular picnics and drag grills into the park and listen to a few sets by local musicians. After going for 57 years strong, it is among the longest-running music festivals and draws in the best of local, regional and touring bands.

Behind Orton Park stands the ever-strong Marquette Neighborhood, a pride that dates back to the park’s inception. According to Orton Park’s nomination to the National Register of Historic Places, shortly after Orton Park opened, the residents held a lantern celebration that drew thousands of people to the park to watch the festivities. A gentleman there remarked as he stepped into the park, “The push of these sixth warders is not equalled by the people of any other part of the city. It is barely possible that if they set their minds upon it, it would not rest until they had the capitol out here too.”

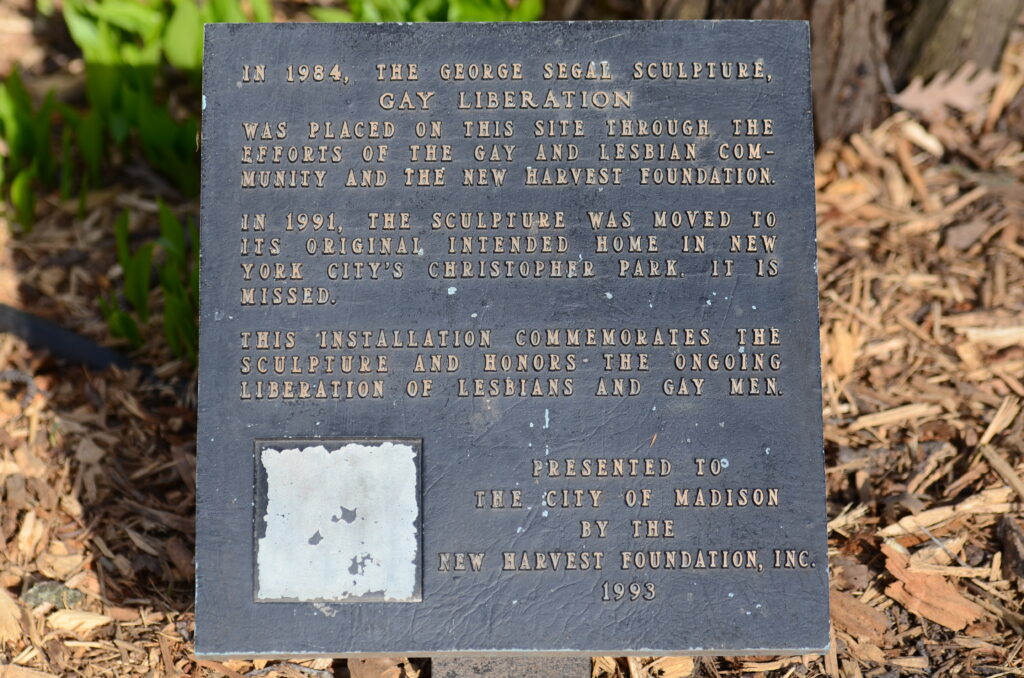

In 1984, Orton Park welcomed a new, impermanent resident, a statue entitled “Gay Liberation,” by artist George Segal. The installation depicted two gay couples, two men standing and two women sitting, made of bronze and painted white. It was originally intended to be displayed in Greenwich Village in New York to commemorate the Stonewall uprising, but the city failed to fund the project. Queer organizers in Madison then successfully raised funds and petitioned the city to have the sculpture placed in Orton Park.

While in Madison, “Gay Liberation” was vandalized on at least one occasion, but it was also embraced by many community members, some of whom placed hats and scarves on the figures during cold Madison winters. In 1991, the statue was moved to its original intended home in Christopher Park in Greenwich Village. A plaque where the statue once stood commemorates the history of the statue in Orton Park.

On a windy Monday afternoon, Mickela Heilicher, who plays professional ultimate frisbee with the Milwaukee Monarchs, and Jack Kelly, who is also a professional player with the Madison Radicals, tossed a disk in an open area at the park’s north end. It was Heilicher’s first time at the park, but Kelly, who lives in the area, had visited before.

“I rollerblade around. I go on night walks as well. This is nice, just like, crossing through and just being by the lake,” he said. Neither Kelly nor Heilicher knew that they were tossing a frisbee on what used to be a cemetery. “I’m not superstitious,” Heilicher said. Kelly said he has never encountered anything spooky on his night walks through the park.

Given its history, some Madison residents believe that Orton Park is haunted. Sherry Strub, who authored the book “Ghosts of Madison, Wisconsin,” wrote that many, herself included, have a feeling of unease while in the park at night.

“The trees in the park are the most mentioned as being haunted,” she wrote, adding that there were reports of ghostly figures lurking around the trees, watching passersby.

Orton Park may or may not be haunted by ghosts, but it is certainly full of the spirit of its past. Its many trees recall what used to be a forest, then a cemetery, then a park. Plaques and decades-old structures remind park-goers of the land’s historic moments. And, whether they know it or not, every person who passes through Orton takes part in the living history of Madison’s first park. Orton Park is one of Madison’s deepest roots in its history, proof that the old and the new can coexist and complement one another.

This collection of stories by professional master’s students in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication explores a series of first experiences, contributions and movements across Dane County.