While working on wrongful conviction cases, it’s rare to receive good news.

But when good news does come, Cristina Borde said her work — even though it might take decades — is worth it.

In mid-March, Borde found out her very first client as a defense attorney in California — a case she took on 20 years ago — got his conviction overturned. Vincente Benavides was facing the death penalty but had maintained his innocence. In a unanimous decision by the California State Supreme Court, he got his murder conviction reversed.

“That was someone I feel very strongly about and a family I knew very well,” Borde said. “It was a unanimous decision which is extremely rare. That was a career highlight and just really exciting. It makes me feel like the road may be long but…[there is] a chance to succeed.”

Currently, Borde is a supervising attorney at the Wisconsin Innocence Project housed in the University of Wisconsin-Madison Law School. She moved to Wisconsin six years ago after working in California defending clients on death row for 14 years.

When people see news of convictions being overturned, it’s common to think exonerations happen all the time, Borde said. When in reality, there’s a lot of people who the Wisconsin Innocence Project can’t help due to the waitlist.

Borde said there’s almost 200 people currently on the waitlist.

But when the Wisconsin Innocence Project was first founded it had a different problem — finding its first case.

The Innocence Movement

The Wisconsin Innocence Project was co-founded in 1998 by John Pray and Keith Findley after the two heard of a project in New York looking at DNA in old cold cases. This was the beginning of what later would be termed as the “Innocence Movement.”

Pray said the two of them weren’t sure what they’d find and if there were wrongfully convicted individuals in Wisconsin. For the first three years, the program didn’t have any luck, Pray said. It wasn’t until 2001 until the program got its first exoneration.

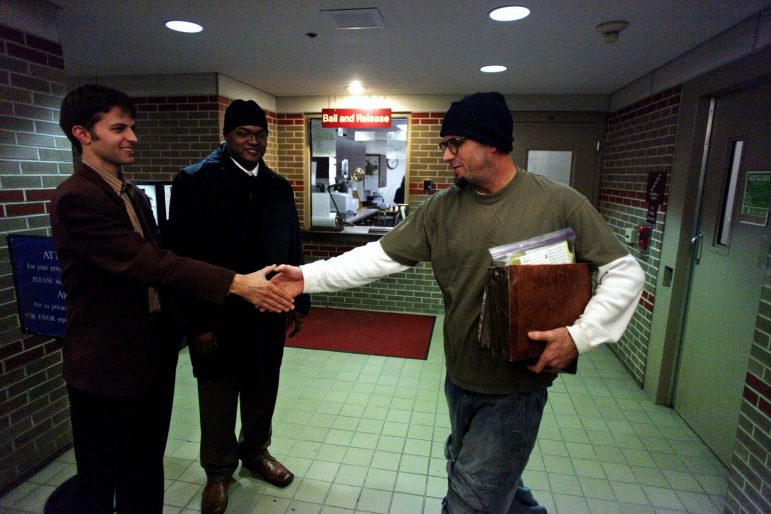

“Our first exoneration was a Texas case. We were one of about four or five programs in the country, so because of that, we decided to take a case outside of Wisconsin,” Pray said. “Once we got that first [case,] the program exploded in the sense of publicity. All of a sudden there was a lot of attention given to the Project.”

The Project’s first exoneree was Christopher Ochoa, who was convicted in 1989 of a rape and murder he did not commit and released 13 years later. Ochoa falsely confessed after being threatened with the death penalty and interrogated in two 12-hour segments.

Under the right conditions, people falsely confess to crimes when under duress, which is backed-up by research, Borde said. False confessions are present in 12 percent of wrongful convictions in the U.S., she said.

The publicity led police, lawyers and other actors in the criminal justice system to reach out to Pray and Findley and ask where investigations went wrong so the same mistakes aren’t repeated.

Pray, who has been retired for more than a year, said he and Findley were happy to share their knowledge and provide training or seminars to the various groups to discuss the patterns not only in Wisconsin but in cases across the country.

In addition to working with Madison Police Department, Findley is working on research to reform eyewitness identification procedures and ways to improve forensic science evidence.

Since the start of the project, the Wisconsin Innocence Project has exonerated more than 20 individuals.

However, when Borde began working for the Wisconsin Innocence Project she noticed a discrepancy in the data of who is helped by innocence projects.

Disparities for Latinos

African-Americans make up 38 percent of inmates and 46 percent of exonerations. White inmates make up 40 percent of the population and 39 percent of exonerations. But Latinos, who make up 21 percent of inmates, only make up 12 percent of exonerations.

Based on those disparities, Borde applied for a grant from the federal Department of Justice. When she received the grant in 2016, Borde founded what is now known as the Wisconsin Latino Exoneration Program.

“A lot of my Latino clients, especially…people who didn't grow up here and moved here, they just find the criminal justice system so foreign,” Borde said. “It goes beyond language issues, although that is a big part of it.”

Borde grew up in Colombia and both her parents are Colombian. Being bilingual and bicultural has been an asset during her career.

With this grant, supervising attorney Maria de Arteaga said the goal is to have more outreach to Latino inmates who might not know about the services available to them.

Serving as a bridge for non-native English speakers and the criminal justice system and translating that information is really important to Borde. Even for people who are native English speakers and have lived here their whole lives, the criminal justice system is hard to understand, she said.

“Being able to give [Latinos] access to the system and to defend their rights and champion their cause and explain to them really thoroughly what's going on to me that's incredibly important,” Borde said. “I think that's where a lot of failings are in the criminal justice system. Or people just don't understand the system…and their rights aren't really well-represented because of that.”

Struggles after exoneration

Out of all 50 states, Wisconsin has the lowest compensation law for exonerees.

Under state law, individuals who have been wrongfully convicted receive $5,000 for each year they were wrongfully imprisoned with a maximum of $25,000. In other states, such as Michigan and Ohio, exonerees receive $50,000 and $40,330 per year, respectively.

The Wisconsin statute was passed in 1913 and amended in 1987. Since then, the law hasn’t been changed.

State Sen. Van Wanggaard, R-Racine, introduced bipartisan legislation in December 2017 to increase the compensation law and provide transitional services for exonerees.

The bill proposed increasing compensation to $50,000 per year with a maximum of $1 million, which is more comparable to other states, Borde said. In addition, the bill looked to provide job training, housing assistance and health care to exonerees — services not currently offered for wrongfully convicted individuals in Wisconsin.

“If you are someone who’s guilty…and you’ve been released, [Wisconsin has] a number of transition programs available to help reintegrate into society and help find housing, jobs, health insurance — a number of things that are important to all of us,” Borde said. “None of those transition programs are available to exonerees. Once their conviction is vacated and they’re released from prison, they don’t get any of that which makes absolutely no sense.”

The bill also focused on providing health insurance so exonerees can get access to the health care and mental care they need, something Borde said is critical. A lot of exonerees struggle with finding their place in society and suffer from trauma of being imprisoned and away from family, she added.

Borde said a common misconception is everyone who gets exonerated receives compensation, but that’s not the case.

After the individual is exonerated in Wisconsin, he or she needs to file a petition to the Compensation Board and prove their innocence with clear and convincing evidence — a very high burden to meet, Borde said.

If the case has DNA evidence, this burden might be easier to meet, but in a lot of cases, there isn’t DNA available, Borde said. Of the 140 exonerations in the U.S. in 2017, 17 cases had DNA evidence and 123 cases did not have DNA evidence.

The bill looked at lowering this burden of proof to preponderance of the evidence, which is the burden that needs to be met in a civil lawsuit, Borde said.

Borde said this was the fourth time legislation like this has been introduced, and even though it fell through again, she believes it will be reintroduced in the next legislative session.

A frustrating, but rewarding, battle

Despite the many uphill battles that come with this line of work, de Arteaga said she feels victory when the project is successful with clients.

The amount of hope and gratitude people express after having their case reviewed is rewarding, she said. De Arteaga is also inspired when she hears exonerees share their stories.

Even though it’s frustrating not to be able to help everyone who reaches out, Borde echoed de Arteaga’s sentiment.

“I've always felt very strongly that I have been very fortunate in my life and I’ve had a lot of opportunities. Many others have not had that good fortune, and I feel it's very important to use my skills and my experience to be able to champion the rights of people who have not had those opportunities. That's something that motivates me quite a bit, and I feel really strongly about.”